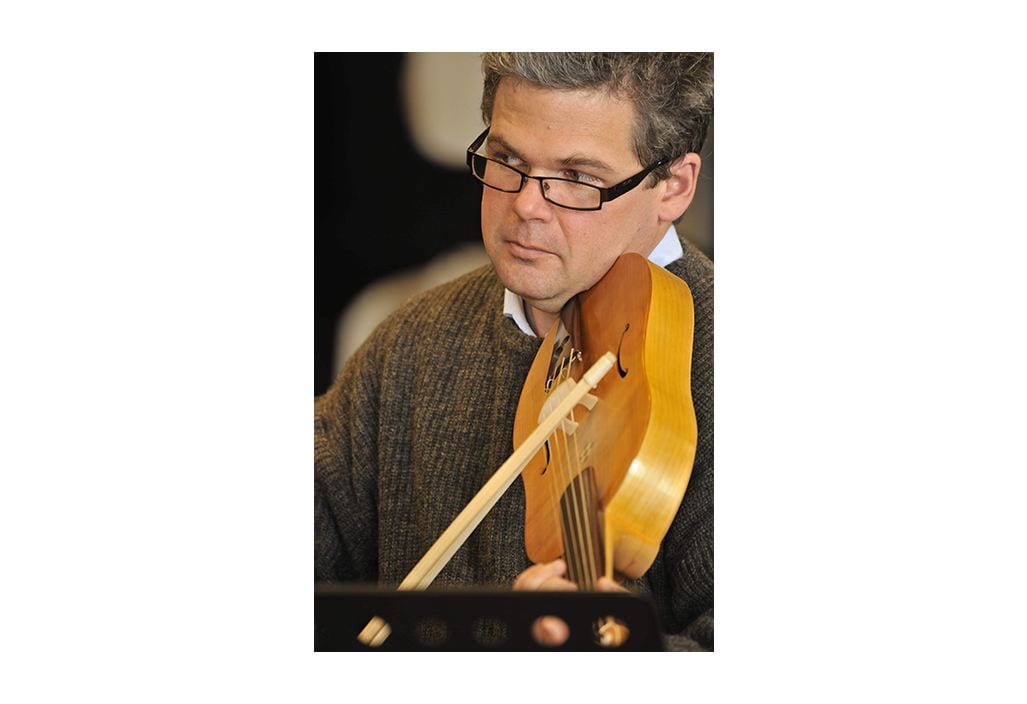

Jason Stoessel, Senior Lecturer, UNE Music:

“I had thought during most of my school years that I would pursue a career in science or engineering. Only towards the end of my schooling did it dawn on me that a career in music was not beyond my grasp. Despite a late start, I studied and practised the violin hard, and successfully auditioned for a place in a music degree.

I remember vividly the moment 28 years ago that changed everything for me: early on in my university music studies, a lecturer played a recording of some music by Guillaume de Machaut, a composer from the fourteenth century. This music was like nothing that I’d heard before and it resonated with me in unexpected ways.

That was the beginning of my long fascination with medieval music, on which I’ve built a career as a music historian. Medieval music research was strong at UNE, so I completed honours and a doctorate here. With a visiting scholarship to the University of Oxford, I was able to research medieval music manuscripts in many of the great libraries of Europe.

I’m now a senior lecturer in music at UNE. As well as teaching, I spend quite a bit of my time researching important developments in European music from the medieval period: a time of exciting and unprecedented musical innovation.

One of the greatest musical inventions of the medieval period was the canon, which is where a melody is combined in strict imitation with itself. Several of the techniques for composing canons were highly experimental, such as combining a melody with the same melody sung backwards and reversing the direction of a melody.

Canons weren’t just about pushing the boundaries of possibility. They were also important for conveying philosophical and religious ideas in medieval and early modern culture. For example, a canon consisting of three voices was sometimes used to represent the Trinity in music written for the Christian church.

Musicians have always admired the craft of composing a canon, yet not a single description of how to compose a canon has survived from the first 200 years of its history. With a grant from the Australian Research Council (ARC) in 2015, I’ve been able to explore the more than 2,000 surviving examples of a canon from the era, working out the rules for composition by unravelling a very old type of musical notation that few people read today.

As part of this research, Dr Denis Collins (University of Queensland) and I have catalogued every type of canon from 1330 to 1530 for the first database of its kind, at canons.org.au.

I’m now exploring the resurgence of canons in early seventeenth-century Rome, a period more commonly associated with the emergence of novelties like opera and instrumental music. But rather significantly, the radical experimentation in canons from this time parallels the advent of the Scientific Revolution in European society: another historical spike in exploration and innovation! I have spent time in the archives and libraries of Rome and Bologna for this new ARC project, and I expect to return to Rome for further research towards the end of this year.

Learning about the music of the past and other cultures helps us ask questions about the role this art form plays in our lives. I am constantly amazed by how seriously the people of the past took music as a vehicle for expressing some of the most important ideas of the day. Where speech, text and image failed, music stepped in to express ideas, feelings and give meaning to an often tumultuous world.

In my research and teaching, I seek to create understanding, patience and tolerance for different musical cultures. Though today’s listener is the inheritor of many past traditions, it would be wrong to stake any personal claim over them. Rather, learning about old music teaches people to listen differently, to think differently and to grow as human beings. With this knowledge comes the realisation that the world we know is not the only one: the human condition is subject to continuous change and self-actualisation. Ultimately, recognising the subjectivity and contingency of one’s existence leads to better musicians, more rounded individuals and better members of society.”

Image: Jason Stoessel plays a reconstructed ‘vielle’ or ‘viella’, a medieval instrument. Photo by David Elkins.

Recent Comments