Image: Nagai Tokusaburō, Grandson of Nagai Takashi and Director of the Nagai Takashi Memorial reading room, photograph, 2016 | This article is written by Dr Gwyn McClelland, Lecturer in Japanese Studies at UNE.

Have you ever wondered what happens to collective trauma as eyewitness memory fades? For descendants of eyewitnesses, do the wounds of violence dissipate, vanish, or evaporate? Can we move on from events of history in following generations – forgive and forget as it were – after those directly affected pass away?

Actually, scholarship shows that traumatic or extreme experience endures, with a viscous hold on people and place. In fact, there is new and emerging evidence about the varied ways impacts of trauma burden the following generations. At the same time, the new generation are not passive in their inheritance of such complex memory.

A Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, Marianne Hirsch, confronted the above questions as she examined writing and visual culture after the Holocaust. She developed an apt term, postmemory, to grapple with the discussion of ‘memory’ work in public history, which continues unabated after eyewitnesses pass away.

After carrying out an oral history survey interviewing twelve atomic bomb survivors in Nagasaki, I proceeded to write a book, but continued to wonder about these questions of Hirsch about the future of memory-work. For myself, I was interested in their relevance in the aftermath of the atomic bombing of this city. I interviewed second and third generation ‘children of the bomb’ to further analyse these questions.

I became aware that even among atomic bomb sufferers in Nagasaki, there was evidence of an older postmemory, due to earlier persecutions the Tokugawa and then Meiji governments in Japan had carried out against ‘Hidden Christian’ ancestors, up to the year 1873. In my new article on this topic, which has been published in History Workshop, I discuss Hirsch’s concept of postmemory from this Asian-Catholic perspective, in remembering the atomic bombing of this city. I argue the affective nature of transmitted trauma and memory has resulted in new and influential generational participation in heritage and public history.

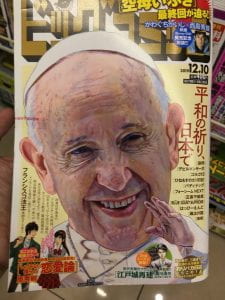

The ‘mixed history’ of Nagasaki and its beginning as a Christian town are important to its distinctiveness. As a partial result of Hiroshima’s domination of much of the literature about the atomic bombings of Japan, the Nagasaki Catholic minority, located around Ground Zero to the north of the city, is little known outside of Japan. Yet this city was developed as a Christian city by Jesuit missionaries in the sixteenth century, and for a period, denoted as the Rome of the Orient. In the twenty-first century, Pope Francis in 2019 made his own pilgrimage here where he held a Mass for the faithful.

Pope Francis depicted on a Japanese ‘manga’ magazine, 2019, Photo, The Author.

There is an influential connection from the atomic aftermath to a communal “Hidden Christian” discourse referring to the period of a Christian-ban, including memory of sacred sites of trauma, and of valorised endurance. Postmemory of the atomic bomb in Nagasaki is highly influenced by such earlier imaginative memory-work of the Catholic community.

Matsuo Sachiko, who was eleven years of age when the atomic bomb was deployed by the United States army, explained to me how she understood her own suffering of the bomb alongside her grandmother’s survival of a forced exile and persecution as a child in the early 1870s. In 2018, UNESCO listed twelve new sites as Hidden Christian sites of World Heritage Outstanding Universal Value in the Nagasaki region, which I have also written about recently here.

Postmemory relates to the haunting of trauma’s afterlife. The rupture or scarring represented as a ‘black hole’ is also evident for new generations. The grandson of Nagai Takashi (Tokusaburō: Photo above) lost all connections to his mother’s family and therefore to the Hidden Christians due to the atomic bombing. Of those I interviewed among Catholic sufferers of the bomb, I’ve written elsewhere about the orphans including those who lost and lament their mothers. Their lament is itself as an example of engagement in the ‘imaginative investment, projection and creation’ of the postmemory discourse (Hirsch).

Another second-generation sufferer who I discuss at length in the History Workshop article heard his father tell about the experience of the atomic bomb, and became a Christian as a child before he knew that he had Hidden Christian ancestry. His investment in his identity associating with his ancestors increased as he learnt more about the history of the city. He related that more than a Japanese man, he identified as a ‘Child of Nagasaki’.

Recent Comments