The archaeological process is a long and painstaking one. It can take years, if not decades, from the moment of a project’s inception, to the release of the final report. In many cases the report is the end of the process. The archaeologist moves on to (hopefully) bigger and better things. The site gets backfilled or completely destroyed/overprinted by development. The report, which may be the only remaining tangible evidence of the investigation, can become tangled up by commercial-in-confidence clauses, or lost on a dusty shelf. This begs a fair question that we archaeologists should always ask: what was the point? If, barring a local news story or a site tour, the result of all that work is a report that nobody sees, let alone reads, was it worth the time and treasure? I, dear reader, am pretty cynical. I have seen – and been part of – work that goes nowhere, a flash in the pan that does not advance the case for Australian historical archaeology. People get excited about the process of excavation – the mud, blood and tears – but the impacts of archaeological investigations have to continue well beyond the time spent on a site.

Australian archaeologists have agonised over impact for decades, with the questions asked 30 years ago still having currency today. Great steps forward have been made, with reports being made available in the digital realm. However, across Australia, there are few jurisdictions that make data available in such a way. Some don’t even have a set policy for data storage, which of course begs the question: if nobody knows where the data is, how do we query it?

During the course of an investigation, public-facing initiatives like this blog, taking advantage of media interest and public talks can all make the research palatable to a wider audience – albeit restricted in their longevity and reach. In the Academy, we seek some form of longevity through publication in journals, however the reach of these is often terribly limited. Months are spent crafting papers that – at best – a few hundred of our fellows will read. Unless you want to spend thousands of dollars you don’t have on making articles Open Access (such as this one here!), the interested public are locked out of reading such treatises.

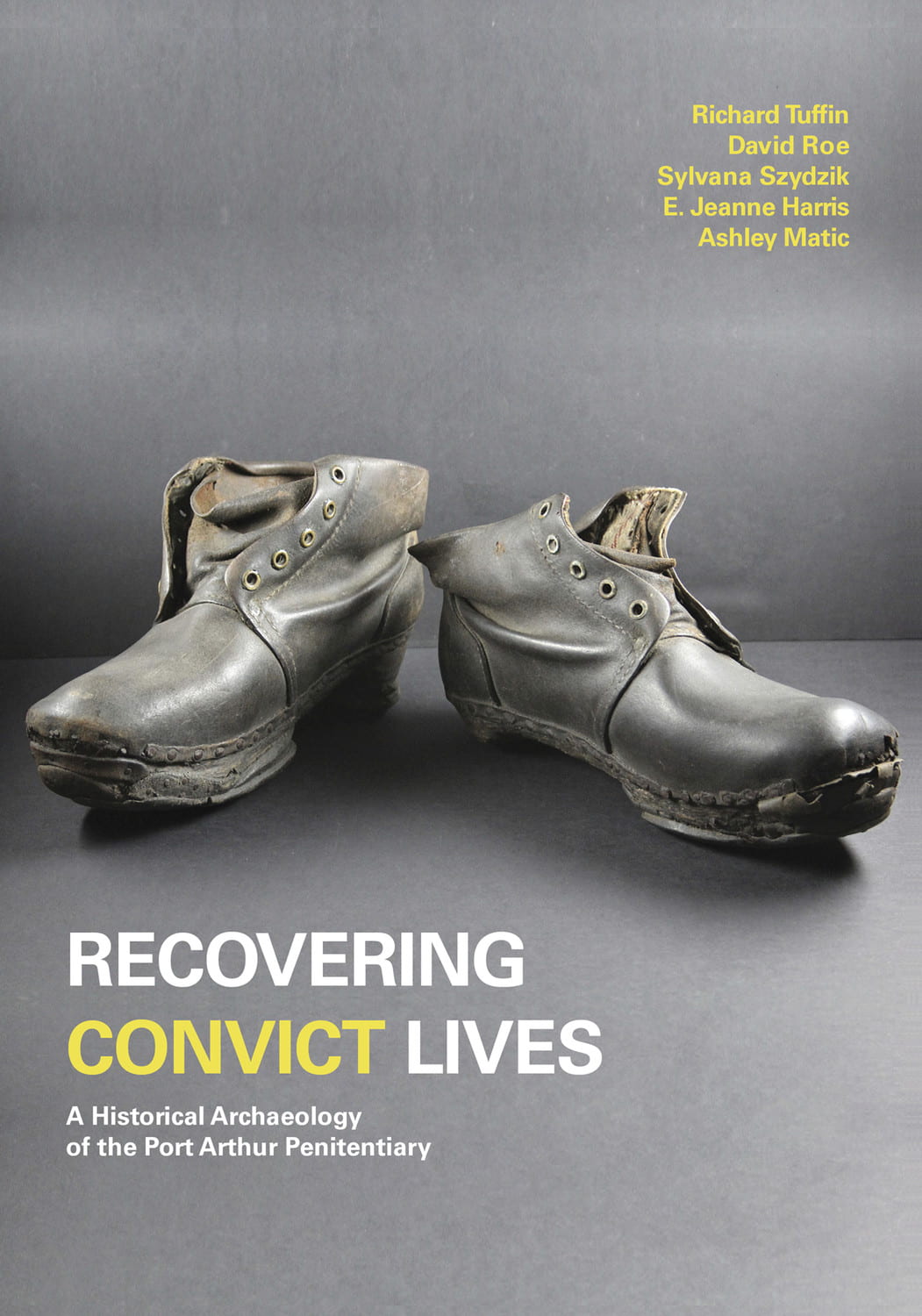

This all brings me to the point of this update. We have a book coming out! Books have both LONGEVITY and REACH. They can form the definite exclamation point of a long archaeological program. In our case, it’s a book that has been over seven years in the making, covering the excavations of the Penitentiary precinct at Port Arthur between 2013-16. As I said, the archaeological process is a long and painstaking one. It’s a joint work between myself, David Roe, Sylvana Szydzik, E.Jeanne Harris and Ash Matic.

Published through Sydney University Press, as part of the Australasian Society for Historical Archaeology’s monograph series, the book takes you on a journey of discovery. It might even possibly change your life. I quote (myself):

The World Heritage-listed Port Arthur penitentiary is one of Australia’s most visited historical sites, attracting over 400,000 visitors each year. Designed to incarcerate 480 men, between 1856 and 1877 thousands of convicts passed through it. In 2016, archaeologists began one of the largest ever excavations of an Australian convict site. Recovering Convict Lives: Historical Archaeology of the Port Arthur Penitentiary makes their findings available to general readers for the first time. Extensively illustrated, it is a fascinating journey into the inner workings of the penal system and the day-to-day lives of Port Arthur convicts. Through the things they left behind – the sandstone base of a prison wall, a clay pipe discarded in a washroom, gambling tokens dropped between floorboards – this book tells their stories.

One of the main aims of the book is to make the results of all this work accessible and understandable. Archaeological reports are dry – full of numbers and tedious descriptions. I write them, but I don’t read them. This book tries to strip all that away, attempting to interweave the research results with a story of the place and the people. Most importantly, there’s lots of images: more maps, plans, illustrations and photographs than you can poke a stick at. Archaeological work is incredibly visual – so why not take advantage of that.

The book is out in November. It is, in fact, the perfect stocking-filler.

Hi Richard

I look forward to seeing a real BOOK. I have no need whatsoever but after following your dig I wondered how I would get on without it, so now I can drop a big hint on my Christmas list. I hope nothing holds up the publication. Best wishes to all of you.

That’s very kind! Never fear, there’s a lot more work to happen on the investigation – so much work.

Currently there’s nothing holding it up…but things do happen…

Congratulations to Richard Tuffin, David Roe, Sylvana Szydzik, E. Jeanne Harris, and Ashley Matic

Recovering Convict Lives

A Historical Archaeology of the Port Arthur Penitentiary

Kind regards

Linda

Indeed. Thanks!