Much like the unwanted appearance of The Candyman, saying ‘artefact’ on a historic site more than once will summon these nasty critters. Dozens – nay, hundreds – of them will come squirming out of the ground, gnashing their sharp little teeth and wailing unmentionable litanies of the lost and damned. The only recourse for the brave archaeologist is to confine them in plastic bags, the suffocating sweatiness of which will usually placate these hellish beings. Once herded together in a spotless lab, the fun really begins…

As you can possibly tell, not all archaeologists are dazzled by the pretty things. I myself prefer the the act of unravelling and recording challenging stratigraphic sequences: how a site has formed and developed over time. It’s quite a buzz when you piece together a sequence of occupation, working out how humans have modified the natural and cultural environs to suit their purposes. However, very often it’s the artefacts that make the news. Humans love treasure. They love to find it. To see pictures of it. They love to see pictures of archaeologists smiling through their tears as the cameraman makes them hold up a piece of broken glass or the stem of a clay pipe…or a trowel full of dirt.

It’s ok. Before you get upset, I know how important artefacts are to the story of the site. They help us date deposits. They can tell us where and what people were doing in spaces. As objects made by human hands, artefacts themselves can tell us about how humans related to each other and their environment. What they thought about the physical and metaphysical world. They can tell us about operational process: from the attainment of raw materials, to construction and discard.

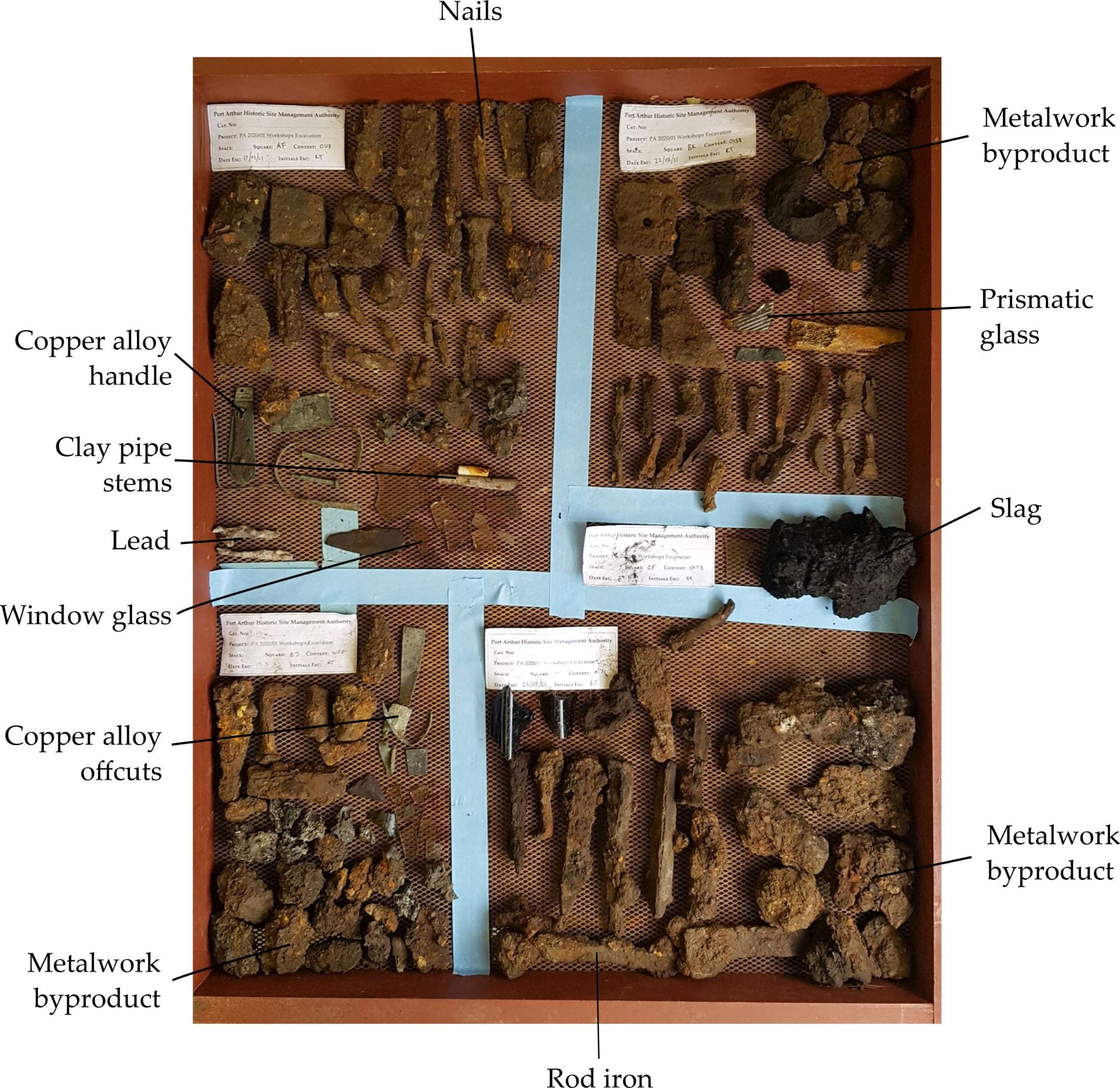

The excavation of the foundry and blacksmith is resulting in a large amount of artefacts. The vast amount of these relate to the byproducts of industrial process. This is exciting, because it can eventually tell us about the efficiencies of this process. Copper alloy and iron offcuts, discarded and broken tools, crucible sherds, slag from copper and iron re-melting, coal dust, a smithing floor. These have all been found across the site. Much smaller quantities of non-industrial artefacts, like fragments of clay pipe, window and bottle glass, have been found. This is not particularly surprising – we’re excavating an industrial site after all.

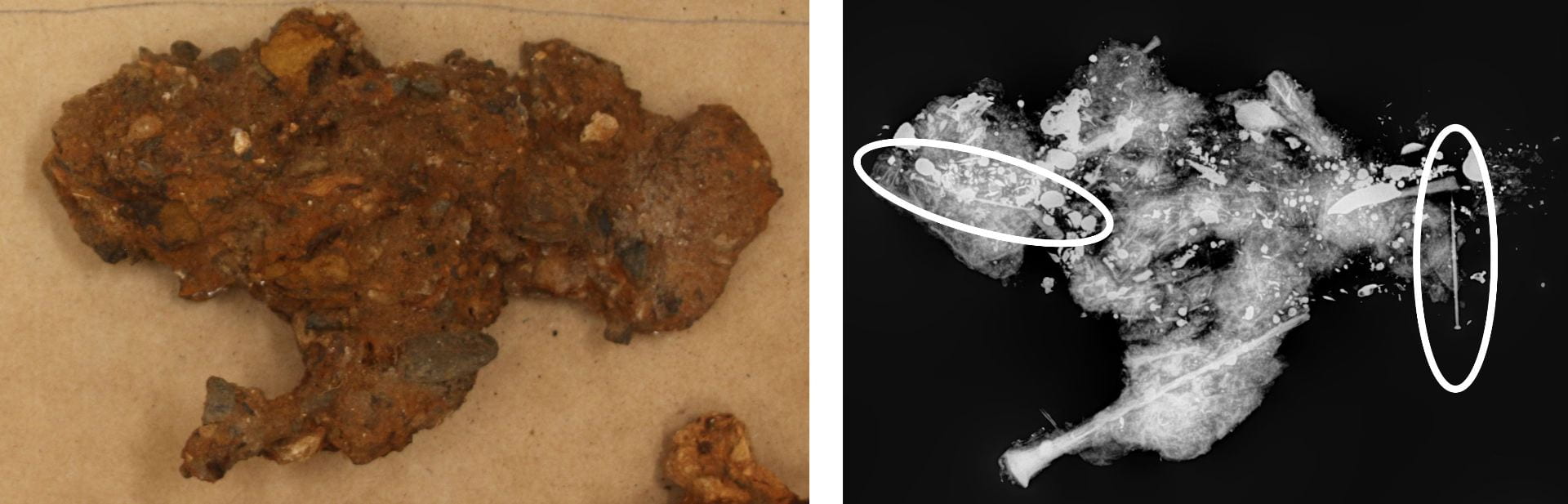

When we find artefacts, we bag them according to context (where they came from in the stratigraphic sequence) and sometimes square (the workshops is divided into a few hundred 1m x 1m squares). If the find is particularly interesting and diagnostic, we will record it as a spot find with the Total Station. The bags then go up to the lab. Here we clean them and sort them onto drying trays. Metal artefacts will be bagged and stabilised in nitrogen, before they take a trip to the radiographer to get x-rayed. Though a bit of a faff, this process arrests the deterioration of metal objects, while taking an x-ray means that we get a much better view of objects which often are covered in concretion.

Once cleaned, the artefacts are then entered into the catalogue. This assigns an object, or group of objects, a specific number, to which a host of attribute data is then assigned: material, possible function, weight, dimensions, maker etc. This then creates an easy-to-use and query database of all the finds on the site. When linked to the spatial information derived from the survey, we can begin to build up a picture of how the site was used and where particular events may have taken place.

From a blob to…something useful. The image on the right shows the pins hidden in the concretion (PAHMSA)

As we move into the post-excavation phase, we will be having to spend a lot of time on analysis. Certain artefacts, like the slag byproduct, will need specialist analysis to examine the metallic composition. Similarly, the hundreds of soil samples will be analysed for the trace elements they contain, as well as examined for the presence of hammerscale (a byproduct of working at an anvil). Like the analysis of the artefacts, this means we can build up a comprehensive picture of the activity areas across parts of the site, helping us deduce where certain activities may have taken place.

Yeah, artefacts might be a pain, but they sure are useful.

Fascinating process!

Hi Linda. Glad you think so! Parts of it ARE fascinating.