It’s been a very busy three weeks – hence you have not been hearing from R Tuffin. However, don’t despair – I am back. Back with news and some views. These last weeks have seen us aided by archaeologists Caitlin D’Gluyas and Martin Gibbs. Both are my colleagues from UNE: Caitlin is undertaking a PhD looking at the boys’ reformatory of Point Puer and Martin is the all-knowing Professor of archaeology. With their very competent help, we’ve been getting stuck into the foundry deposits.

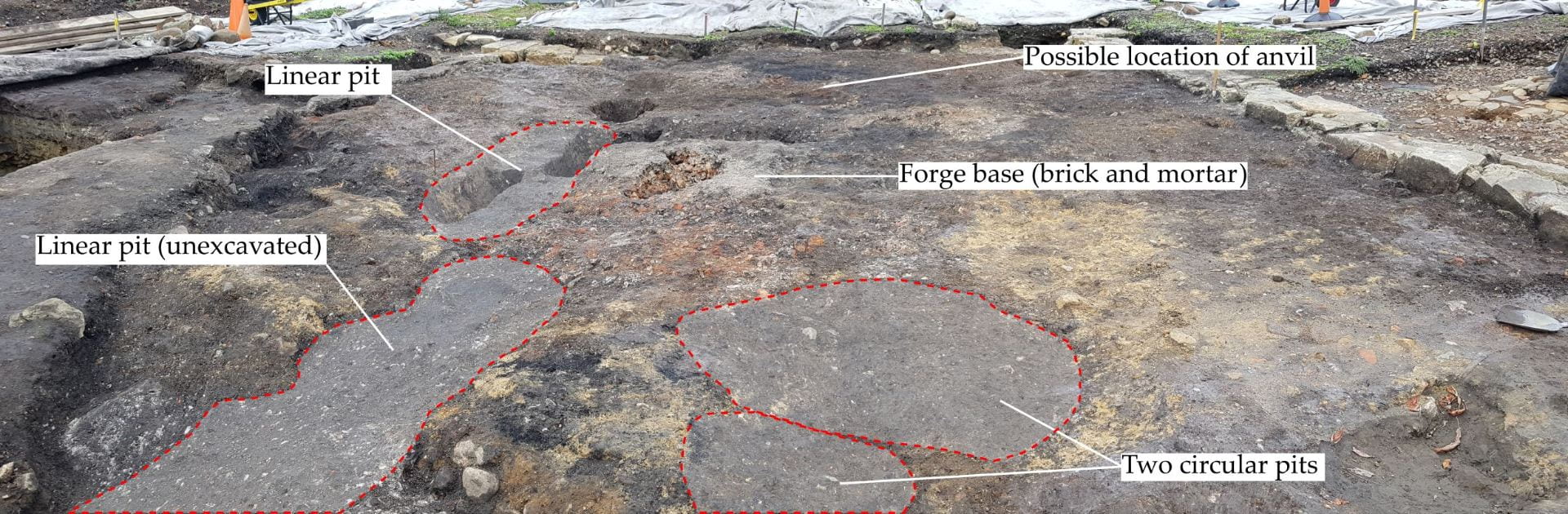

The first thing we got up to was a major ‘clean’ of the whole space ready for a new round of photogrammetry. This process involved making sure all loose soil was removed from across the area, which was also lightly troweled to bring up the colour changes- it’s an art form. As you can see from the photographs, the foundry space presents a riot of colour: with dark, charcoal-rich silts in the eastern half (the left of the above photograph), bright yellow sandstone and clay in the centre and mid-brown silty clays in the west. This is likely indicative of the space being used for different purposes (such as hot work in the eastern half, with the west being used for work away from the forge).

Once the photogrammetry was complete, we started excavating a series of intrusive features (pits, linears and postholes). Sylvana and myself began excavating two large (<2.0m) linear features near the central forge base. Currently we still have little idea what these represent. The linear pit adjacent to the forge base appears to have been excavated to facilitate the construction of the forge itself, the base of the pit having a lot of mortar that seems to have run off the top of the forge base when it was poured. The other pit is more of a mystery. It too had a lot of mortar – though more bricks were situated throughout. These bricks were quite early in origin – being quite large in size and of a red/reddish orange colour (usually a hallmark of the bricks made in the 1830s at Port Arthur). One possibility we are looking at is this linear pit once contained features (like a wall footing) pertaining to the construction and occupation of the earlier 1830s workshops. This may have been removed during the 1850s conversion of the workshops, resulting in the rubble-filled pits we see today.

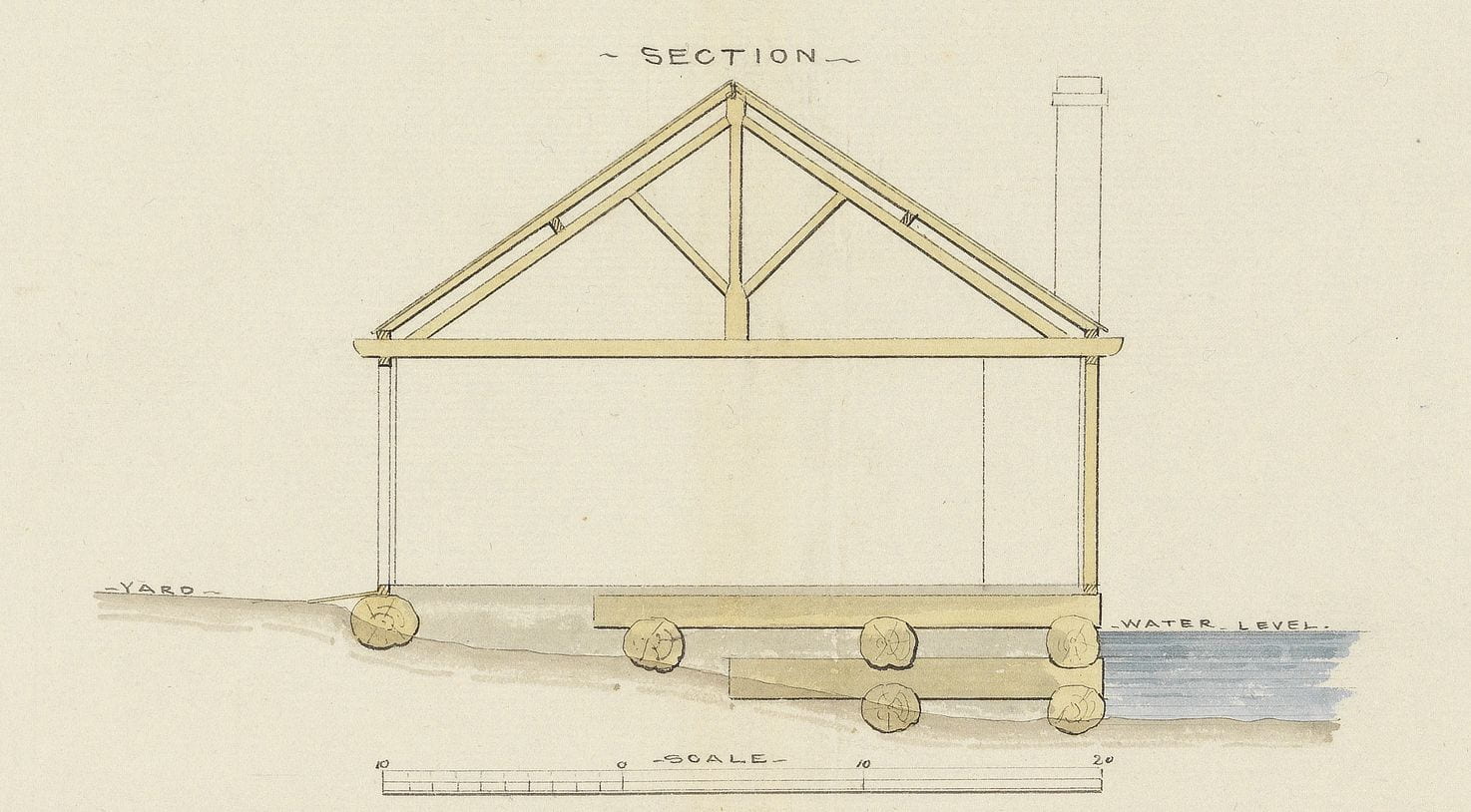

Laing’s section through the workshops, showing the log cribbing forming the reclamation (Henry Laing, ca.1836, Tasmanian Archives)

Another distinct possibility is that these linears represent subsidence of the early reclamation. They correspond neatly with the reclaimed area depicted in Henry Laing’s 1836 illustration of the workshops (above). This shows a series of large logs beneath the workshops. Previous excavation underneath the Penitentiary has shown that these logs have a tendency of rotting away, causing the ground above to subside. We have evidence of subsidence across the northern half of the site, with features like footings sunk into the ground at odd angles. Our linears may have been formed when these logs gave out along their length – with the subsequent pit filled with whatever rubble was to hand. Anyway, that’s my theory.