The following is adapted from the cunningly-titled 2005 treatise Penitentiary Workshops: Historical Analysis (Greg Jackman, Richard Tuffin), PAHSMA. Available from no good bookstores.

A series of maps have been included. If you want to know more about how the site evolved, visit our online map Convict Labour Landscapes: Port Arthur 1830-77.

1.1 Introduction

The waterfront area, extending from the mouth of Settlement (Radcliffe) Creek to front of the Commandants garden was subject to numerous periods of development. With each pulse of progress in the settlement, this area underwent significant change and remodeling.

The workshops which stood during 1856 to the end of the settlement’s penal life, were built on top of an earlier range of workshops, which were themselves a modification of an initial workshops range. The occupations practiced in the shops mirrored in part the industrial progress of the settlement. From blacksmiths and shoemakers during the early 1830s, to a smithy, tailor, carpentry, cooper, wood turner, shoemaker and nailer by the 1850s, the development of the workshops reflected a widening skill-base and a movement of the settlement from its reliance on import, to a state of self-sufficiency and, eventually, exportation. The apex of this was the workshops which stood during the life of the penitentiary. Housing carpenters, coopers, painters, blacksmiths, foundrymen the workshops also contained a circular and vertical sawmill, powered by a steam engine housed within the same complex. This reflected a widening of timber operations during the 1850s that saw the timber-getters pushing further and further into the surrounding bush to extract the raw material.

1.2 The waterfront workshops

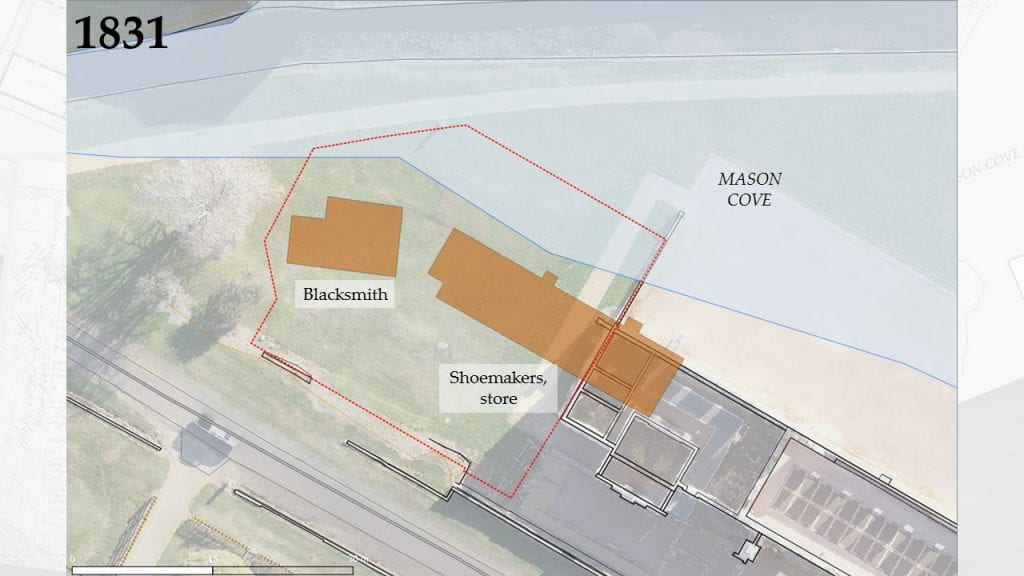

During the initial phase of settlement, the southern portion of the cove witnessed a concerted building program as the infrastructure of industry and goods transport was constructed. The first survey plan of Port Arthur, drawn in 1833, shows a wharf already in place to collect the incoming and outgoing goods. Also on the southern foreshore, to the west of the wharf area and just below the barracks complex, was a range of workshops, constructed in 1831. Housing the blacksmiths and shoemakers at Port Arthur, these purpose-built structures were a clear indication of the authority’s intention to make Port Arthur a working penal station. All tiers of secondary punishment – from the ironed timber gangs to the semi-skilled shoemaking gang – were to be remunerative to the station.

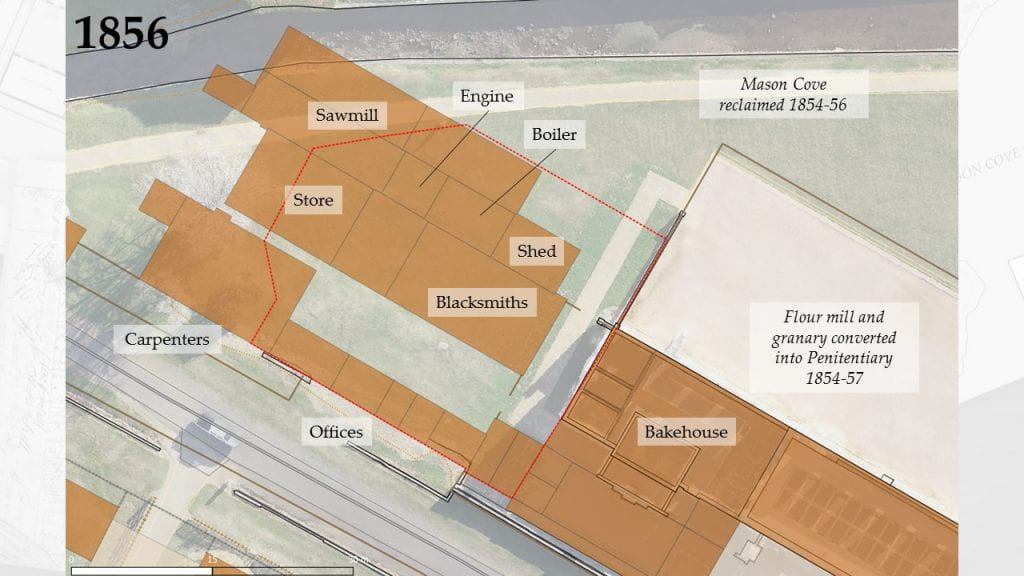

Soon after the settlement of Port Arthur in September 1830 a store and blacksmiths was built on the site (excavation area outlined in red)

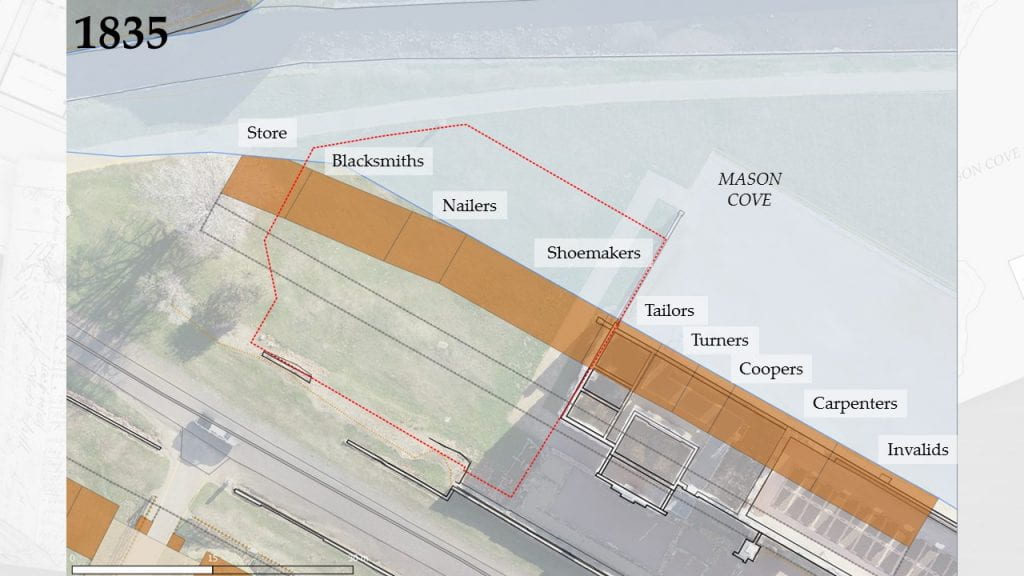

During the mid-1830s the penal settlement experienced a rapid population growth, with its incarcerative and industrial capacity consequently increased. By 1835 the shops had been extended to incorporate stores, smiths, nailers, shoemakers, tailors, carpenters and coopers. The workshops housing these trades was likely an extension of the pre-existing structures, the new building a renovation and refit of the old. As part of this it was likely extended slightly to the east, and the gap between the old smithy and shoemakers shops built-in to form the nailers shop.

By 1835 the workshops had been extended, the structure likely incorporating the two former buildings

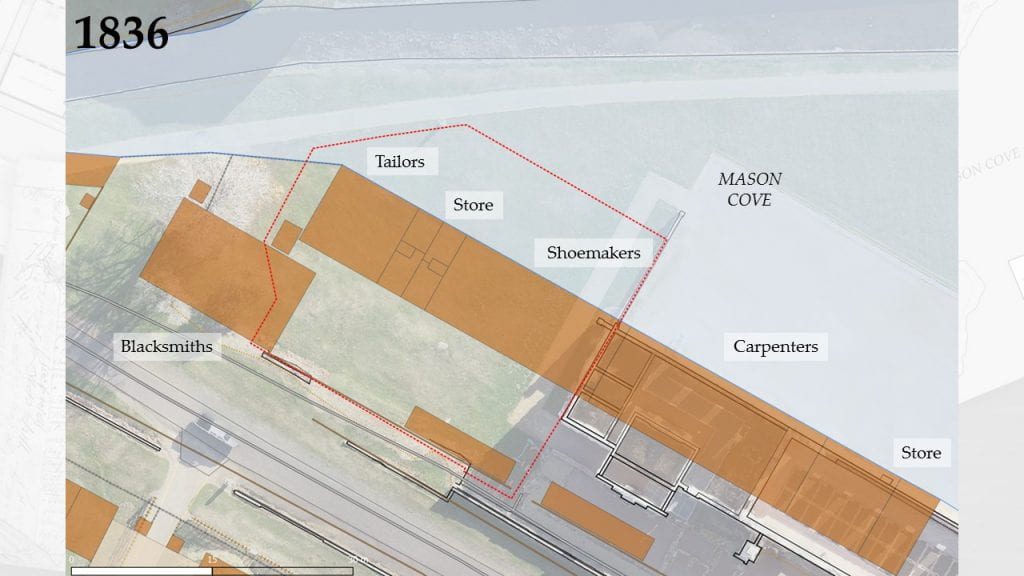

By 1836 the workshops had once again been remodelled and extended, with a new blacksmiths building added behind the main row. In this year the buildings of Port Arthur were recorded in detail by convict draughtsman Henry Laing, meaning that we have a good idea what the workshops buildings looked like and what they contained. The blacksmiths were constructed from sandstone, with a hipped shingle roof from which a large ventilator protruded. The shop was fitted with nailers’ benches, two double forges and three nailers’ benches. The main workshops were built from timber weatherboard and shingle and were founded mostly on land that had been reclaimed from Mason Cove.

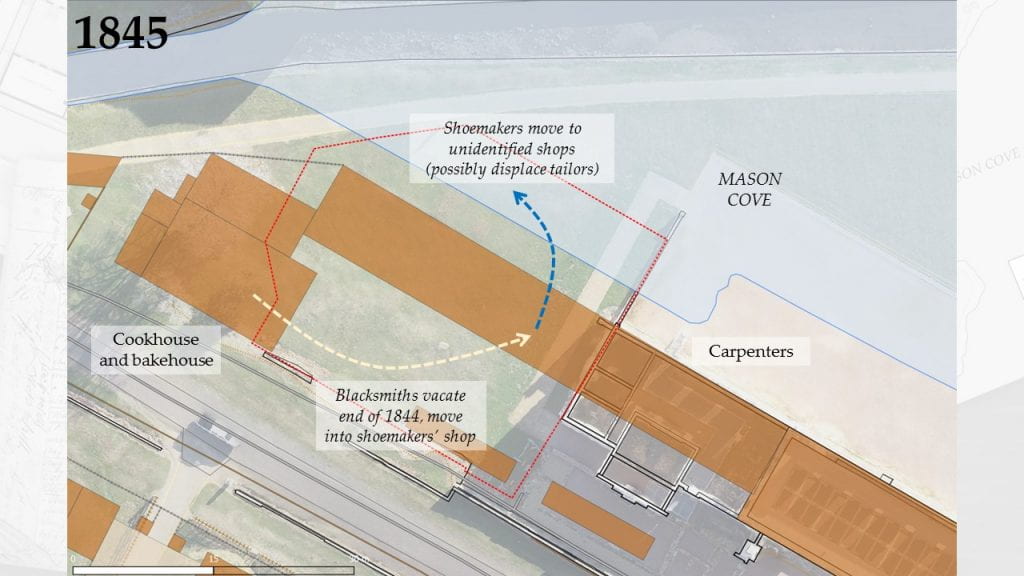

Plans in 1841 indicate that the shops underwent further modification after 1841, with the addition of a large separate building at the western edge of the range, as well as a number of smaller huts. This was necessitated by the construction of the flour mill and granary in 1842-45, which truncated the workshops at their eastern end. As part of this, the blacksmith shop was moved to a new location in 1844, likely the shoemakers’ shop in the workshops range. This vacated the shop at the west end of the range, which, in the 1854 plan, was occupied by the cookhouse and bakehouse.

The conversion of the flour mill and granary into a penitentiary during 1854-57 had a marked impact upon the workshops. In July 1856 the Commandant reported that the buildings comprising the workshops area would be completed within a matter of months. By August, 1858, the workshops were listed as still under construction, though the steam engine had been completed. A year later the workshops and mill complex had been completed, the only other building under construction being the engineer store in the mill building. All buildings were finished by 1860.

A post-1863 plan gives us a good level of detail as to the internal divisions of these two workshops. The northernmost building contained the sawmill (with both circular and vertical saws), bone mill, their attendant boiler room, blacksmith (with foundry), wood shed, and engineer store. The southern workshops, separated from the mill building by a mechanics’ yard, contained the carpenters, coopers and painters. This configuration apparently continued until the settlement’s close, with an 1870s plan showing the only change was to the southern building, where a basketmakers’ shop was opened next to that of the carpenters.

1.3 Winding Down

The penitentiary conversion and the construction of its attendant infrastructure was part of a wider growth in the 1850s which saw an unparalleled growth in infrastructure. The timber industry increased at an immense rate as men and material from the closed Cascades timber station were funneled back to Port Arthur. This resulted in the 1856 erection of the sawmill in the penitentiary workshops. Agriculture too took an upturn with the 1852 completion of the settlement farm. The penitentiary housed all the prisoners engaged in these vital tasks.

However, by the early 1860s, wind no longer filled the station’s sails. The 1853 cessation of transportation began to be felt during this decade, as colonial offenders began to be redirected through different punishment channels. Port Arthur was left with a population slowly ageing and becoming less effective. With the slow degeneration of the prisoner population, less and less reason to house convicts in the penitentiary could be found. The heavily manual occupation of timber-getting could no longer be carried out. Nor could the large-scale agricultural production. The penitentiary was not built to house paupers or invalids and eventually the remaining prisoners were shifted to the pauper and invalid accommodation.

This resulted in an attendant downturn in maintenance of the penitentiary complex, a fact that was borne out by the comments of a visitor in 1876, who noted that “…the wood-work and especially the flooring [of the day room and lavatory] was going to rack and ruin.” The degradation was complete by 1889, when a correspondent for the Tasmanian Mail, recorded how the ‘weatherboard erections’ adjacent to the penitentiary had completely collapsed and were overgrown with weeds. An 1889 survey plan shows the workshops area as completely vacant, the laundry and day room evidently still standing in some form or another.

The penitentiary was not sold in the 1889 land sales, the asking price of 800 pounds obviously being considered too high. The matter was taken out of everybody’s hands when, on December 31, 1897, the penitentiary was gutted by fires. The timber ablutions block and what remained of the laundry, would have stood no chance.

From that point on, the main issue was with the safety to tourists of the slowly degrading structure. No construction took place in the laundry and ablutions block, the space being left open until the late 1960s when, during 1967-71, a concerted works program was undertaken to stabilise the building. This saw the space being used for the parking of heavy machinery and storage of building materials.

The workshops space was witness to more activity. During the early 1930s a large wooden shed was built to house the museum pieces of William Radcliffe, storekeeper and landowner at Port Arthur. His museum, along with G.R. Eldridge’s museum, the Hotel Arthur (in the old Junior Medical Officer’s residence), the Commandant’s House hotel and a group of guides served the swarms of tourists visiting the site during the early 20th century.. Radcliffe filled his museum with curiosities dug up from around his property – including penitentiary space. With Radcliffe’s death in 1943, management passed to his widow, who moved the museum outside of the historic site. The old museum was then leveled in 1959 and left to grass over.

just visited the site – looks like an impressive dig albeit rather muddy at the moment.

Is it a mill stone – if i follow the blog then I’ll find out more.

good luck and thank you for sharing

Lindy

Hi Lindy. Rain is one of the perils of digging through autumn/winter/spring – especially in Tassie. The site is partially reclamation, so it appears to drain very nicely. Ah, yes. The question of the stone. I will do a post on that at some point. We have not idea. Millstones tend not to be made of sandstone, as you would get sand in the meal. It has been suggested it may have been the stone for the bone mill (also in the workshops). We just don’t know as yet – and we may never find out!

Very impressive blog rich.

“The old museum was then leveled in 1959 and left to grass over.” That’s a quote from your article rich. See I read everything …

I love it when you quote me, Old Man