Archaeologists hate the word ‘treasure’. It conveys an image of jolly digging at the end of a day’s quest, or *shudder* metal-detecting. If doing work in a public place, odds are an archaeologist will get asked if they ‘have found any gold/treasure’ yet. Hilarity ensues. We usually like to use less loaded terms to describe the objects we recover: ‘artefacts’, ‘finds’, ‘material culture’. I’ve been pretty happy using those terms for my two decades running about as an historical archaeologist. However, during this excavation we found some ‘finds’ which very nearly made me use the dreaded ‘T’ word.

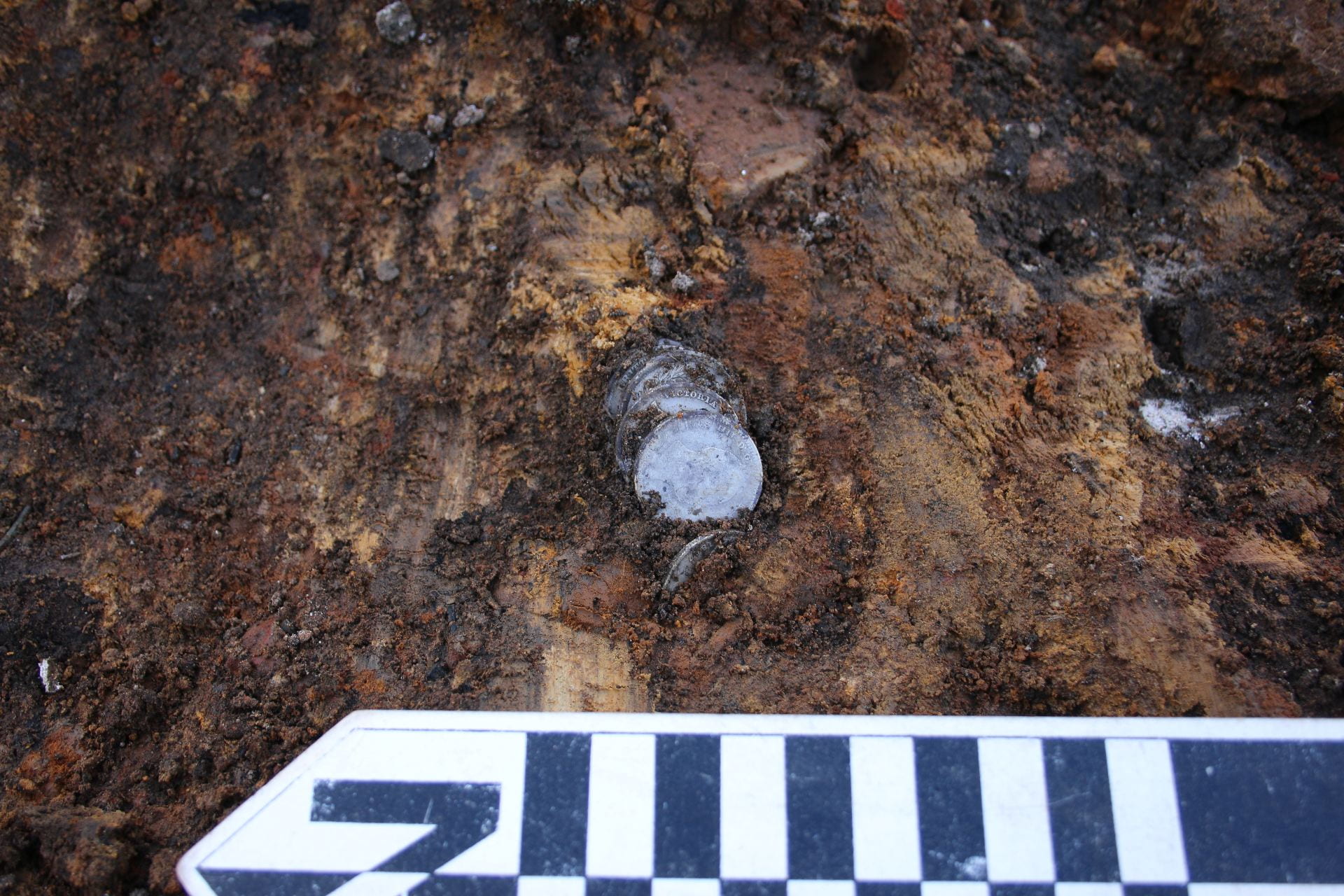

When excavating in the western half of the foundry, digging through a clay deposit that had likely been used as a surface in the copper-working area, we found something rather interesting. As I was wielding my mattock with heroic precision and care I heard the distinctive ‘chink’ of metal on metal. Squinting down through the rivulets of sweat caused by my exertions, I saw the glint of silver. Quite a lot of silver. On close inspection I saw this:

Oh my…

Now, we’re used to finding coins on site. I don’t get too excited about them. They’re handy for dating, but that’s about it. However, these were different. As it turned out, there were 20 of them. All stacked together and set into the clay. “That’s pretty cool” I thought to myself, with uncharacteristic excitement. I almost cracked a smile, but quickly restrained it, lest Sylvana think something was wrong with me.

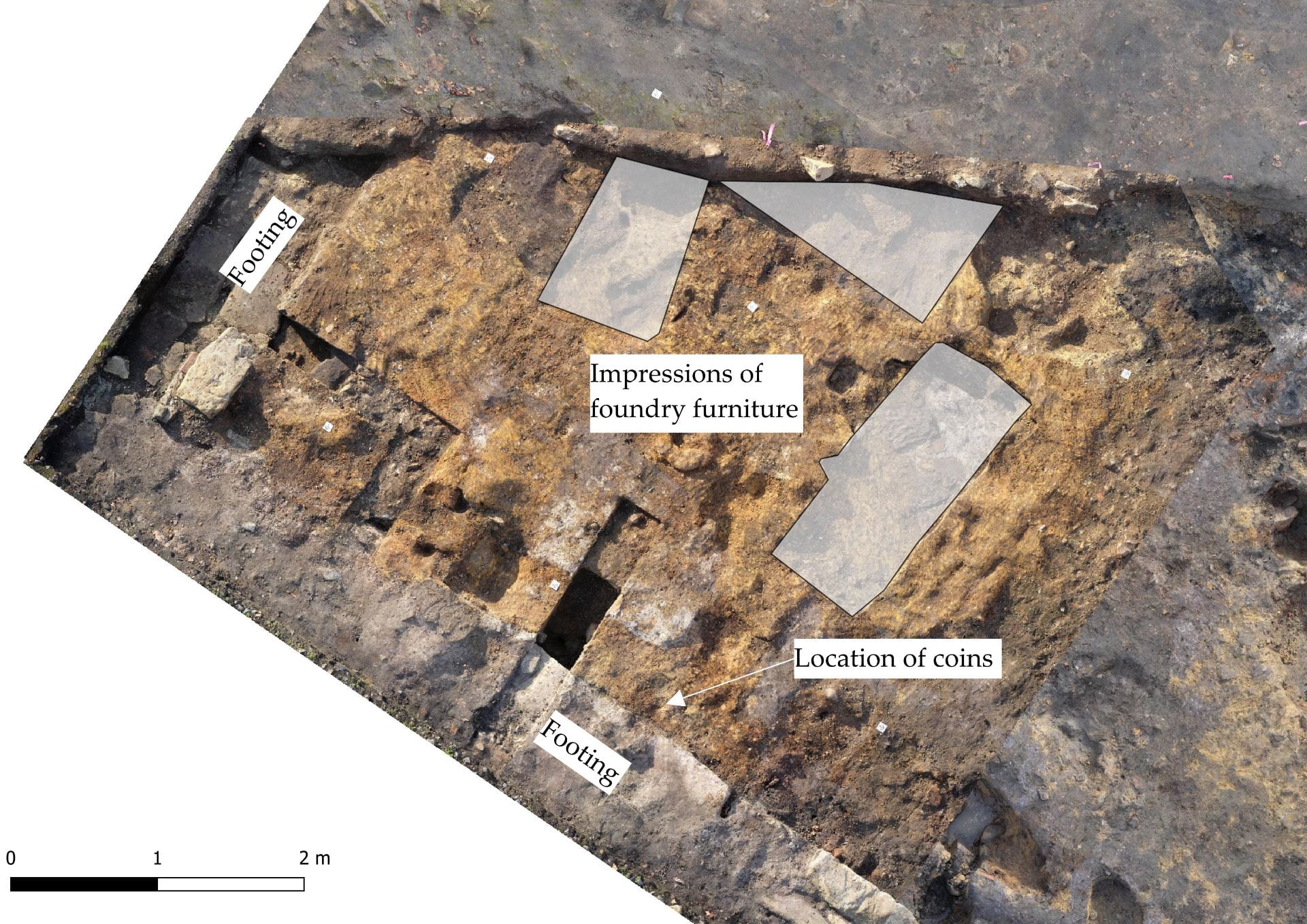

As with all ‘objects’ we’ll never know the story of how these coins ended up in the clay – though we can make a few deductions. They were all deposited at the same time, potentially contained within a roll of paper (the edges around the coins were slightly more humic than the surrounding clay). They ranged in date from 1816 to 1844. They were all silver One Shilling coins. Some of them were very worn. They were situated in an area of the foundry where a number of large pieces of foundry furniture had been situated – we found their impressions set into the clay in which the coins were buried.

A map to excitement

One possibility is that these coins were a convict’s ill-gotten gains, hidden but never retrieved. Convicts as a rule did not have access to money and, when they were found with it, were arraigned before the Commandant for breaking settlement regulations. We know that an Overseer or Constable received from 3 shillings per day – so we are looking at at least a week’s wages. Is it someone’s paypacket (literally) that was pilfered? Why was it never retrieved? If a convict put it there, were they suspected and never allowed to access the workshops again? Remember, only selected prisoners were allowed in this space. It was a space of industry, but the find of the coins also suggest the very human (and unregulated) acts that may have led to them ending up there.

Attack of the shinies

Finally, for me, it’s also a lesson – if one is needed – in why going around wantonly metal-detecting can be such a destructive past-time. Yes, a detector could have found these objects, but what would have been learned? Finding them in context has provided us with an opportunity to think about the operation of the convict ‘underbelly’. Possible stories are constructed – about pilfered money and frustrated plans. We’ll never know the truth, but where they were found, in tandem with how they were found, makes them a priceless find on the site. But no, not ‘treasure’.