Port Arthur – like many convict stations – was built through the exploitation of the landscape’s raw materials. Timber, shell (for lime mortar), dolerite, coal, clay, even seawater (for salt) was extracted, transported and processed to feed the penal industrial beast. All this labour was of course undertaken by prisoners – every board sawn, rock broken and log carried forming a junction between punishment and profit.

One of the more visible impacts upon today’s landscape are the sandstone quarries. Most of the nine major convict stations established on the Tasman or Forestier’s Peninsula (bar Point Puer boys’ reformatory, Flinders Bay and Slopen Island) had convict-worked sandstone quarries situated near the station. Though pre-settlement surveys for a station sometimes identified the stone (if it was outcropping), mostly it took a number of years until a viable source of stone was located, tested and finally opened up to largescale working. At Port Arthur, we think the first such quarry was opened in late 1833 (three years after settlement). We don’t know where the quarry was located, but we know that it was because a part-sandstone building was constructed in that year.

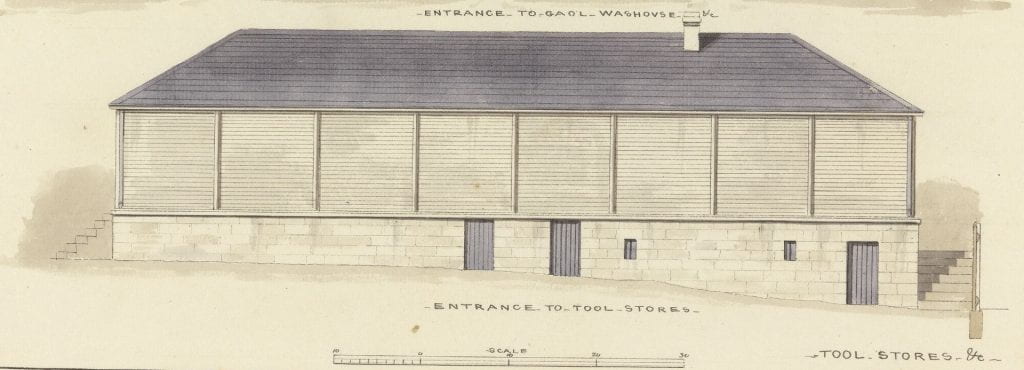

This building was begun in late 1833 using sandstone from the first quarry opened at Port Arthur. Note the use of ashlar stone for the lower portion (detail of: Henry Laing, ‘Tool Stores etc’, ca.1836, CON87/30, Tasmanian Archives)

Sandstone was an excellent medium for constructing buildings at a penal station. Not only did it require the input of skilled and unskilled labour to extract, it created durable buildings that could withstand the depredations of convicts unwillingly locked within them. When a new prisoners’ barracks was proposed for the station in 1846, the Royal Engineer in charge noted that:

The proximity of this site to the Quarry is a great recommendation…the buildings being extensively erected by Stone which would be far better than of brick…(1)

Sandstone provided a particularly useful material for separate and solitary cells. Early cells at Port Arthur, as well as cells later built at Point Puer, were constructed from timber. The men and boys were able to pry gaps in the wall, enabling illicit goods (like rations and tobacco) to be passed to the prisoners. The thin walls also enabled communication, with offence records showing that prisoners were sometimes charged with “singing in the cells”.

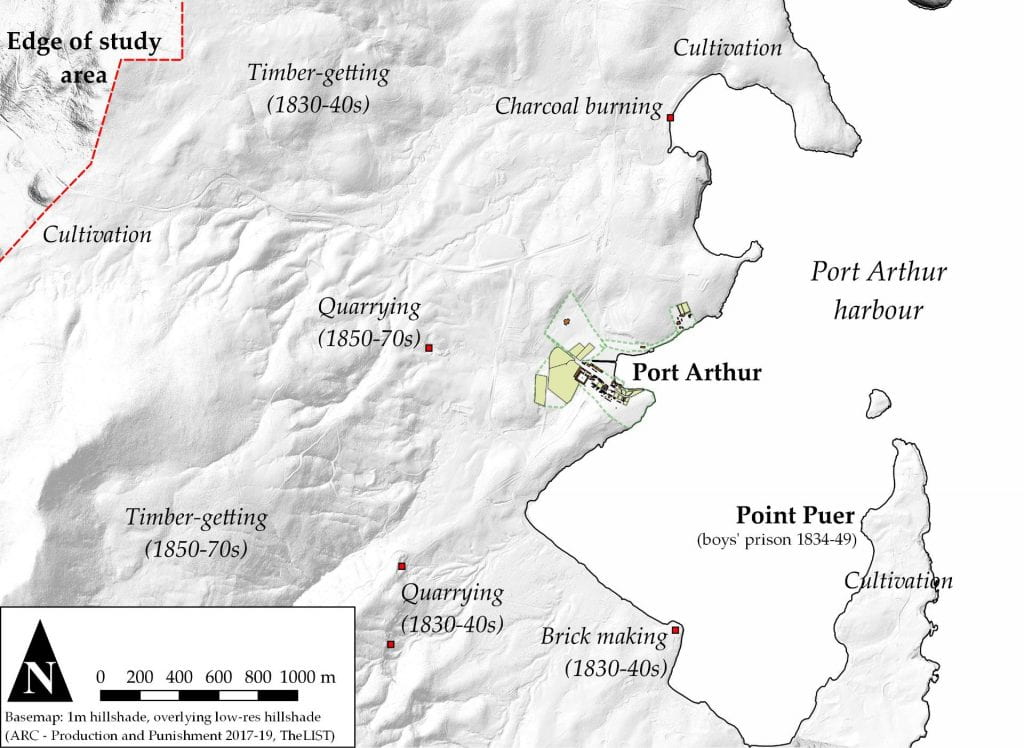

The map below shows the main areas where convicts attained resources around the station between 1830-77. Three main quarry sites are shown. These were huge undertakings, which employed a large number of prisoners at any one time. Returns from 1850 list that 54 men were quarrying stone, probably from the southern quarries. The one to the west of the station was opened in the late-1840s/early-1850s, likely to provide stone for the 1848 construction of the Separate Prison. This provided stone until the end of the convict period.

LiDAR map of the Port Arthur hinterland showing activity areas (see this article)

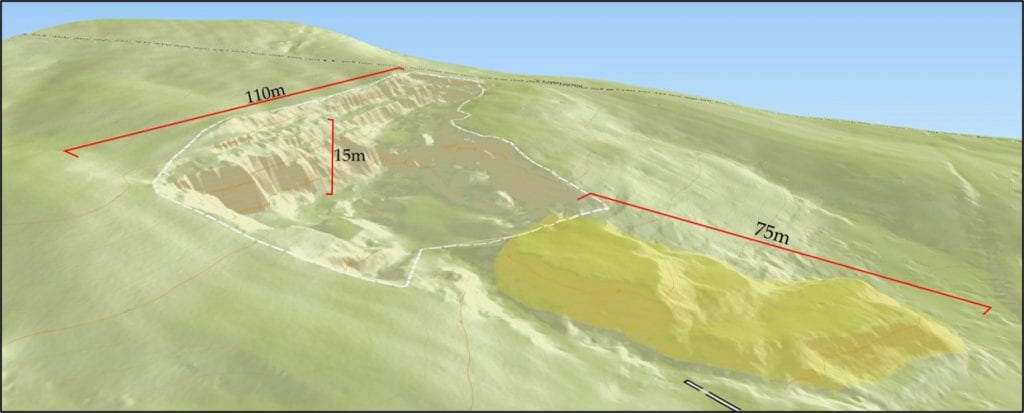

The quarrying of sandstone has left a very noticeable archaeological legacy in the landscape. Quarrying places are formed from interlinked sites, designed to extract, transport and process the stone. There are the quarries themselves, which can range from small test pits, through to massive undertakings. The quarry to Port Arthur’s west is a particularly large example (see below), where the story of extraction can be read in the terraces, exposed faces and spoil heaps. Pick-marks cover the quarry faces, in some cases you can still see the channels cut prior to levering the blocks out with iron wedges. At the western quarry we estimated that 24,000 cubic metres of sandstone had been removed – equating to about 70,000 person days of work for a man cutting ashlar stone. If ten men were kept at work every day, it would have taken them 17 years to quarry that volume.

Leading from the quarries are roads and tramways, both of which were used to transport the stone to the place of processing or shipment. At Port Arthur we think they would have transported unprocessed blocks of stone to the places of construction or cutting. At other places, such as the Coal Mines, finished blocks have been found scattered around the quarry. For the majority of the convict period, men were required to push and pull the carts (both road and tram). In the 1870s, during the station’s ‘welfare’ phase, we know that four horses (Champ, Prince, Punch and Captain) were working the Port Arthur tramroads.

At the station the stone was used for the construction of buildings, cut by masons to provide close-fitting ashlar blocks, or incorporated into random rubble walls. Stone was also used for ornamental purposes, such as the pillars topped by urns which marked the entrance to the Church’s boulevard. In our excavation we found another use for it – as general fill. The crushed sandstone at the base of the trench Sylvana is working in was likely waste sourced from one on the southern quarries and carted specifically to the site to be used as reclamation. Its very yellow colour is also indicative of this southern quarry, which also likely provided the stone for the Guard House (1835), Church (1836) and the hospital (1842). The western quarry provided stone of a lighter colour, used in the Separate Prison (1848-54) and Asylum (1864).

- Archibald Macfarlane, Royal Engineers, to Charles O’Hara Booth, Commandant, 16 May 1844, MM62/17, A1107, Tasmanian Archives.