John M. Malouff and Caitlin E. Johnson

University of New England, Australia

Abstract

This article describes a search for expert-recommended warnings for governments to mandate in commercial gambling. The search involved identifying researchers who have published an article on problem gambling in the past year and at least three other articles on problem gambling in the past five years. All these researchers, along with editors of two gambling research journals, received an invitation to recommend warnings for governments to mandate. The search identified 24 experts, 14 of whom provided warnings. Almost all the suggested warnings fit in one of eight content categories with at least two suggested warnings in each. The warning categories covered these topics: (1) gambling is risky — gamblers will likely lose money and may experience other problems, (2) specific advice about how to minimize losses and avoid problems, (3) reflect on your gambling, (4) gamble only if it is fun, (5) compare own gambling amount with gambling norms, (6) gambling is addictive, (7) avoid emotional gambling, and (8) amulets do not help). Governments could mandate warnings by commercial gambling enterprises to reduce the harms caused by gambling. Researchers could examine possible ways to deliver warning content so as to maximize its effect.

Background

Gambling takes many forms. These include wagering on electronic gambling machines such as poker machines and slot machines, betting on sporting events, gambling at casino games such as roulette and craps, entering lotteries, buying scratch cards, playing bingo for money, and betting on dog and horse races (Welte, Tidwell, Barnes, Hoffman, & Wieczorek, 2016). The betting can be online or in a gambling establishment. All the different types of gambling together produce a total of hundreds of billions of dollars of profit for the enterprises that conduct the gambling (Markham & Young, 2014). Those profits come from the losses of huge numbers of gamblers. As an extreme example, Australian adults lose on average over Aus$1000 per year in gambling (Boyce, 2019).

Some individuals gamble so much that they lose more money than they can afford. These individuals may lose their homes and their jobs as a result of the time and money they devote to gambling. Their family life may collapse; they may experience great anxiety and depression. We can think of these individuals as problem gamblers (Raylu & Oei, 2004). They vary in number from country to country, but they average a few percent of adults across nations (Calado & Griffiths, 2016), meaning that the worldwide total number of problem gamblers is very large.

There are different ways to look at the determinants of problem gambling. When analyzing any type of problem, we can focus on the person involved, the situation, the interaction of the person and situation, or on a combination of these factors (Kihlstrom, 2013). The Reno Model of gambling problems (Blaszczynski, Ladouceur, & Shaffer, 2004), which resulted from a collaboration of gambling researchers and gambling-industry leaders, takes the view that the main problem exists in the person (Hancock & Smith, 2017). Specifically, some individuals make bad decisions related to gambling, act irresponsibly, and become problem gamblers.

The Reno Model is consistent with popular theories of health-related behavior change: the theory of planned action, the theory of reasoned action, the health belief model, the cognitive-behavioral model, and the transtheoretical model. All these models focus on cognitions and decision making (see Gehlert & Ward, 2019). The Reno Model explanation is beneficial to the gambling industry because it tends to absolve the industry of responsibility. Some gambling experts reject the Reno Model and point instead to aspects of the gambling situation as being primarily responsible for problem gambling (Hancock & Smith, 2017). These other situational aspects include gambling legalization, along with the high availability of gambling, including Internet gambling (Gainsbury, Russell, Hing, Wood, & Blaszczynski, 2013; Welte et al., 2016). Efforts to market gambling through advertising and other means may also contribute to problem gambling (Dyall, Tse, & Kingi (2009).

One implication of the Reno Model is that it may be possible to steer gamblers away from problem gambling by helping them view gambling as a recreational activity that requires self-regulation. Hence, warnings about risks might prove helpful. So, in the United Kingdom, gambling establishments commonly warn customers to stop gambling once they stop having fun (Davies, 2019).

It is possible for governments to mandate warnings in commercial gambling, just as governments have mandated warnings for tobacco products (e.g., WARNING: Smoking causes COPD, a lung disease that can be fatal; U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2020), alcohol (e.g., Consumption of alcoholic beverages impairs your ability to drive a car or operate machinery, and may cause health problems; United States Code of Federal Regulations, 2020), and marijuana (e.g., It can take up to 4 hours to feel the full effects from eating or drinking cannabis; Government of Canada, 2019).

Prescription drugs also carry warnings, sometimes mandated by a health agency and sometimes included to fulfill the duty to warn of known dangers (Bullard, 2017). For instance, the popular antidepressant Zoloft has this warning for users included in packages: “A worsening of depressive symptoms including thoughts of suicide or self-harm may occur in the first one or two months of you taking Zoloft or when the doctor changes your dose” (Pfizer, 2013).

Many governments at the state or federal level regulate commercial gambling in various ways to keep operations legitimate and to minimize harm to gamblers. Recently a few governments have mandated that gambling organizations provide gamblers with warnings. For instance, New Zealand requires gambling-licensed organizations to provide signs stating the characteristics of problem gambling and how to seek help for it, including the phone number for a helpline, along with the odds of winning at each type of gambling (Internal Affairs, 2015). The specific warnings mandated include: (1) Spending more on the pokies [electronic gambling machines] than you wanted? Time to cash out? Win lose lose repeat? Don’t get in over your head. Gambling too much? Know your limits. Gamble responsibly.

In Australia, New South Wales mandates signs providing the phone number for a gambling helpline, along with this warning: Think! About (tomorrow, your choices, getting help, your family, your limits) (NSW Department of Industry Liquor & Gambling, 2018). South Australia requires posting of information about a gambling helpline and posting of alternative signs near machines that allow withdrawal of money: Spending more than you wanted? Time to cash out? Win, lose, lose, repeat? Eat sleep bet repeat? Gambling too much? Don’t get in over your head? Know your limits (Signage requirements for gaming areas, undated). The Northern Territory of Australia requires online gambling companies to inform gamblers of the odds of winning, where appropriate; to provide on signs the helpline phone number; and to provide a message to gamble responsibly (Gambling Codes of Practice, 2019).

Mandated warnings may apply to some types of gambling, for example in-person gambling, but not others. Some elected officials and organizations that try to reduce gambling harm have called for more warnings, including on gambling advertisements (Savage, 2018) and video-game loot boxes for children (Keogh, 2019). Loot boxes are rewards videogame players receive randomly; the reward might be something such as an extra power or the ability to customize one’s avatar to suit the player’s esthetic interests (Drummond & Sauer, 2018). Some gambling experts consider the loot boxes likely to push children toward gambling (Keogh, 2019).

Gambling enterprises may provide gamblers with specific warnings without being mandated to do so. For instance, in the United Kingdom, gambling companies often use the slogan, “When the fun stops, stop” (Davies, 2019). Gambling researchers have developed warnings, evaluated them in analog studies, and found them to have positive effects in analog studies. These are studies typically done in a lab with money or some similar prize available.

Gainsbury, Aro, Ball, Tobar, and Russell (2015) developed warnings based on those in use internationally, for example in public health campaigns. They used a sample of individuals at a gambling venue to test immediate responses to eight warnings: (1) Have you spent more than you can afford (2) Is money all you are losing? (3) Set your limit. Play within it. (4) Only spend what you can afford to lose. (5) Do you need a break? Gamble responsibly. (6) Are you playing longer than you planned? (7) A winner knows when to stop gambling. (8) You are responsible for your gambling. About half the participants reported the warnings were impactful.

Ginley, Whelan, Keating, and Meyers (2016) evaluated gambling warnings with a sample of university students in a lab situation. The study examined the effects of these statements: (1 Your next spin has nothing to do your previous spins. (2) If you continue gambling, you will eventually lose your money. (3) Winning is not due to luck. It is random. (4) Are you losing more than you want? Maybe it is time to quit? (5) Are you having fun? Or are you just losing your money? The results indicated that the warning led winning gamblers to reduce their gambling, but it had no significant effect on losing gamblers.

Jardin & Wulfert (2017) used a lab experiment to test two warnings in experienced gamblers: You cannot predict anything in a game of chance. Winning is completely due to chance. The study found that messages that accurately presented the random nature of gambling results decreased risky gambling.

McGivern, Hussain, Lipka, and Stupple (2019) evaluated pop-up warnings in a sample of university students. The lab experiment found that stating the amount of money lost by the person so far in a warning was more effective than a general warning suggesting moderating expenditures.

Munoz, Chebat, and Borges (2013) used a lab experiment to study warnings in a sample a gamblers. The study found that warnings about gambling producing financial or family disruptions produced more fear and attitude change when accompanied by an image of a gambling monster about to eat a gambler.

The warnings described above provide some warning-content ideas and seem capable of stimulating reflection and perhaps even emotional engagement, but lack comprehensive coverage. Comprehensive warnings could be valuable because societies want gamblers to be aware of all significant risks created by gambling. The risks include financial losses, loss of employment, alienation of others, loss of dignity, loss of a sense of self-control, anxiety and depression (Raylu & Oei, 2004).

In pursuit of a comprehensive, engaging set of warning content topics, we sought warnings from a substantial number of experts on problem gambling. We then organized the suggested warnings into content categories.

Method

We sought to identify researchers who are experts on problem gambling. We defined experts as individuals who were first author of at least one journal article on problem gambling in 2019 and who had published at least three additional articles on problem gambling in 2015-2019. We wrote also to editors of two gambling journals as likely experts on gambling in general. We set these standards in the hope of identifying individuals who would be widely viewed as experts on problem gambling. We used an objective method with the aim of avoiding subjective bias in the selection of experts. To find the researcher experts, we used the term “problem gambling” to search documents covered by Google Scholar.

We sent an email to the experts who met the criteria and asked them to send us suggested warnings that they would recommend governments mandate for legal gambling done in person or online. The request message stated: ‘I am writing to experts on problem gambling and inviting them to send me one to five warnings they would suggest governments mandate for online sites and in-person venues that provide gambling opportunities to the public. I invite you to contribute by email reply. You can suggest warnings for gambling in general or for specific types of gambling, such as playing electronic gambling machines, entering a lottery, betting on sports events, etc.’

The search led to 24 experts, 14 of whom (58%) responded with suggested warnings. The experts who offered suggested warnings are, in alphabetical order, Catalin Barboianu, University of Bucharest; Alex Blaszczinski, University of Sydney; James Broussard, G.V. Sonny Montgomery VA Medical Center (USA); Maria Ciccarelli, Università degli Studi della Campania (Italy); Paul Delfabro, University of Adelaide; Maria Jara-Rizzo, University of Guayaquil (Ecuador); Hyoun Kim, University of Calgary; Habai Lopez-Gonzalez, Nottingham Trust University (UK); Philip Newall, University of Warwick; Anders Nilssson, Karolinska Institute (Sweden); Jane Oakes, Monash University (Australia); Jonas Rafi, Stockholm University; Matthew Sanscartier, Carleton University (Canada); and Mark Van Der Mass, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (Canada).

Results

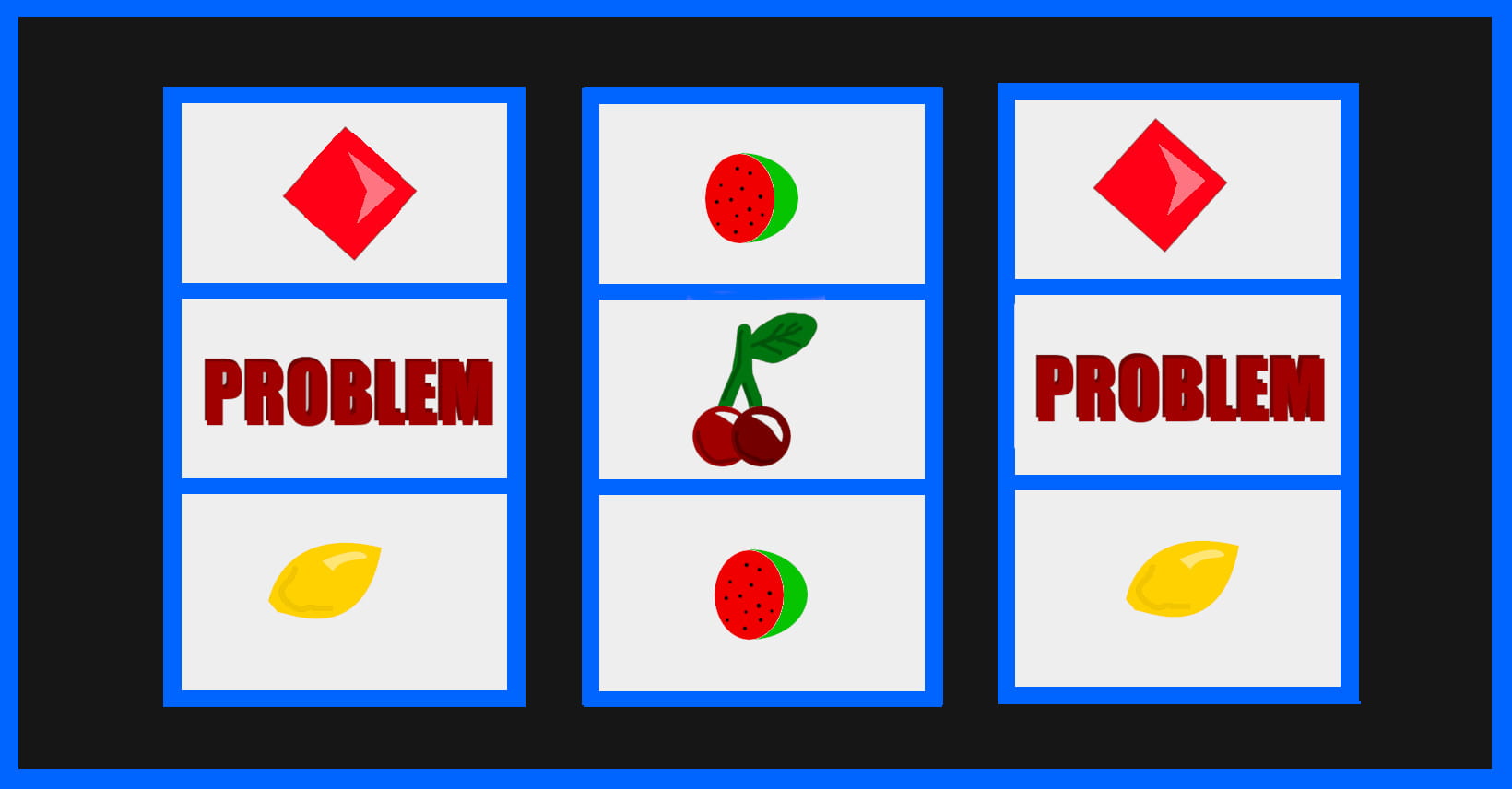

One of us put the 39 recommended warnings in eight logical categories, plus a remainder category. The other author then independently put the warnings into the same categories. We agreed on 34 of 39 warnings (87%) and then reached consensus on the non-agreed warnings. The suggested warnings fit in the following categories with at least two warnings in each category: (1) gambling is risky — gamblers will likely lose money and may experience other problems, (2) specific advice about how to minimize losses and avoid problems, (3) reflect on your gambling, (4) gamble only if it is fun, (5) compare your own gambling amount with gambling norms, (6) gambling is addictive, (7) avoid emotional gambling, and (8) amulets do not help. Three warnings did not fit any of the categories. Table 1 provides examples of specific warnings in each category.

Discussion

Some of the expert- suggested types of warnings provide information relevant to making rational, adaptive decisions about gambling; some ask for self-reflection; some suggest behavior to avoid problems. Some of the warnings, for instance, about amulets, may be more useful in certain cultures than others. The emotional-appeal warnings have potential impact in that they call for reflection about gambling motives. The eight warning categories cover such a range of matters that they might collectively present new or surprising information to problem gamblers. Moreover, they would present new information to potential or new gamblers.

The expert-recommended gambling warnings provide useful ideas for governments about what warnings to mandate. The warnings also provide valuable information to gambling enterprises that want to either reduce problem gambling or to take acts that might forestall government mandates about warnings. At present, the paucity of warnings provided to gamblers suggests that there is an opportunity for appropriate warnings to have a positive impact. Our categorization of the expert-recommended warnings may provide useful information in developing other specific warnings that fit the categories, expand them, or add to them.

There are many types of commercial gambling, ranging from betting on electronic gambling machines online to betting on jai alai in person. Jai alia is a competitive sport similar to racquetball in that it involves propelling a ball against a wall. The great variety of gambling types may make it more complicated for governments to choose warnings than is true for substances, such as alcohol and tobacco. Specific warnings might have different effects on different types of commercial gambling. Or the same warning might be equally effective across types of commercial gambling. Research has not yet provided answers about that matter.

The Reno Model of problem gambling (Blaszczinski et al., 2004) focuses on the decision making of individual gamblers. Many psychological models of health behavior change also focus on cognitions and decisions (see Gehlert & Ward, 2019). One need not subscribe to a cognitive model to view warnings as potentially helpful to gamblers. Mandating or employing warnings does not limit governments or gambling enterprises from taking additional steps to help prevent or remedy problem gambling by regulating gambling promotion and facilitation by gambling enterprises. See Hancock & Smith (2017) for ideas about reducing situational influences that could lead to problem gambling.

Limitations of our search method

Our method of searching for experts on problem gambling did, on its face, lead to experts, but only 14 of 24 responded. These experts may not be representative of all relevant experts and do not represent all cultures. Further, the recommended warnings were not necessarily based on specific research findings. Hence, the suggested warnings may not represent all types of potentially valuable warnings. The types of warnings suggested in this article are best viewed as a step forward in developing expert-recommendations for government-mandated gambling warnings.

Limitations of warnings

In the world of gambling, warnings must compete with psychologically charged aspects of the activity, including pleasantly stimulating lights and sounds, winning (reinforcement), having a chance to win (rule governed behavior), observing others gambling (observational learning), and observing others winning (vicarious reinforcement). See Miltenberger (2016) for descriptions of these psychological principles. Warnings must also compete with emotional (non-rational) influences on gambling, including, for some individuals, the addiction elements of the activity. Additionally, warnings must overcome the power of habit in the case of individuals who are already persistent gamblers. The internal push to repeat a habit occurs with any long-practiced behavior (Wood & Rünger, 2016).

Enhancing the expert-recommended warnings

There is evidence that esthetic appeal for a product can lead to more positive views of the usefulness of the product (Sonderegger & Sauer, 2010). The same might be true for warnings. For instance, the use of esthetically pleasing characters to state the warnings might increase the impact of warnings, at least until gamblers habituate to the characters and warning content. The characters could be similar to those used to market cereal, the Olympics, and other products. Involving a jingle, music, rhymes, beautiful scenes, a personal story, or rapid exciting action might help attract attention and make the message memorable. Such elements would also have the advantage of being surprising or novel. There is evidence that novel or surprising stimuli are more likely to be noticed and liked than other stimuli (Horstmann, 2015; Vanhemme & Snelders, 2001). Gambling enterprises could add that sort of element to the warnings, but they would need help from advertising professionals or other highly creative individuals. They would also need motivation to make warnings memorable.

Research findings indicate that words that are mentally connected to many other words, e.g., “door,” tend to be remembered better than other words, for example “stair” (Xie, Bainbridge, Inati, Baker, & Zaghloul, 2020). Using these more memorable and attention-grabbing words might make warnings more potent.

Characteristics such as graphic content, size, frequency, and how interactive the warnings are could be examined. Munoz et al. (2013) used a scary image of a monster about to eat a gambler. Positive images could also be used, for instance, showing an esthetically pleasing character ceasing to gamble or going home. Use of video and sound could be evaluated. Also, researchers could examine whether presenting information as “warnings” or as “health and wellbeing advice,” “a word to the wise” or some other expression might have useful effects. The more positive the description of the information the more esthetically pleasing it may be.

Overlap with mandated warnings

The expert-recommended warnings overlap to an extent with warnings already mandated by a few governments. For instance, South Australia mandates certain reflection questions relating to financial losses and how to slow them, two topics suggested by experts. New South Wales warns about family effects and provides contact information for help – two other ideas raised by the expert-recommended warnings. However, no government covers the broad range of warnings included in those recommended by experts. These extra categories in the recommended warnings include messages that amulets do not help, encouragement to compare one’s gambling to gambling norms, and prompts to avoid emotional gambling.

Methods of evaluating the recommended warnings

Governments could try to cover all the warning content areas we have identified by categorizing the warnings recommended by experts. More research could help clarify what types of delivery make the warnings believed, remembered, considered personally relevant, and effective in reducing problem gambling.

Research studies have examined in analog studies the effects of warnings with similar content to some of those suggested by experts. For instance, studies have examined warnings about financial costs of gambling, effects on family members, providing contact information for help, as well as reflection questions (Gainsbury et al., 2015; Ginley et al., 2016; Jardin & Wulfert, 2017; McGovern et al., 2019; Munoz et al., 2013). The existence of evidence that many of the types of expert-recommended warnings have positive effects in analog studies is promising. However, there is no evidence with actual gamblers in a natural gambling situation to show what type of content, if any, would have positive effects such as preventing large losses, long playing times, and flow-on negative social effects.

Gambling establishments could operate experiments to test different warnings, but they have little incentive to do so. Researchers could ask gamblers whether they think that specific warnings would reduce problem gambling, but that prediction is a hard one to get right for both gamblers and gambling researchers.

Testing possible warnings in analog (simulated gambling) settings may be the best feasible evaluation method. The external validity or generalizability of these findings is unknown. It is also possible to collect less formal evaluative information about possible warnings in different settings by asking problem gamblers whether they understand the warnings, believe them, and tell them something they do not already know, as has been done with regard to tobacco warnings (Malouff, Schutte, Frohardt, Deming, & Mantelli, 1992). Ultimately, time series analyses might evaluate mandated gambling warnings, as was done with tobacco warnings (Young et al., 2014), but these analyses do not prove causation because other factors can lead to changes over time.

Conclusion

Some governments and pro-social organizations are eager to reduce the harms caused by gambling. These worldwide harms are substantial (Calado & Griffiths, 2016). Mandating warnings is one means some governments use to reduce the harm. Government branches that operate gambling enterprises could use the warnings. Commercial gambling enterprises might voluntarily provide warnings either to reduce problem gambling or to avoid further regulation.

At present, not all types of expert-recommended warnings are being mandated or used. The warnings recommended by the experts in this article have value in that they provide a reasonably comprehensive collection of content types that governments could mandate and gambling enterprises could use voluntarily. Our creation of logical categories for the warnings may prove useful to researchers who develop and evaluate different types of warning content. Because mandated warnings have a low cost to society and to gambling establishments, it may be worth expanding the content of the currently mandated warnings and evaluating the expanded set across the many types of regulated gambling.

To motivate gamblers to heed warnings and moderate their gambling, the warnings may need to be novel, surprising, esthetically pleasing, or contain memorable words. These qualities may help the warning have an emotional impact and stay in the mind of the gambler.

It is not easy, however, to evaluate warnings. Experiments are feasible with simulated gambling, but not with actual gambling. Also, it is hard to find problem gamblers to include in experiments. Other evaluation methods mostly involve collecting descriptive data such as whether the warning is noticed, believed, remembered, and potentially effective. A combination of experimental methods with simulated gambling, combined with mostly descriptive methods, may be the best possible means of evaluation for potential warnings. Time series analyses might be useful to evaluate warnings actually applied in commercial gambling.

References

Boyce, J. (2019, June). The lie of ‘responsible gambling.” The Monthly, https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2019/june/1559397600/james-boyce/lie-responsible-gambling

Blaszczynski, A., Ladouceur, R., & Shaffer, H. J. (2004). A science-based framework for responsible gambling: The Reno model. Journal of Gambling Studies, 20(3), 301-317.

Bullard, M. C. (2017). Put your money where your medicine is — an overview and update on manufacturers’ duty to warn and direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. American Journal of Trial Advocacy, 41, 63. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00018

Calado, F., & Griffiths, M. D. (2016). Problem gambling worldwide: An update and systematic review of empirical research (2000–2015). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5, 592-613. https://doi:10.1007/s10899-016-9627-5

Davies, R. (2019). The Guardian. Warning message on gambling ads does little to stop betting – study. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/aug/04/warning-message-on-gambling-ads-does-little-to-stop-betting-study

Drummond, A., & Sauer, J. D. (2018). Video game loot boxes are psychologically akin to gambling. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(8), 530-532. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-018-0360-1

Dyall, L., Tse, S., & Kingi, A. (2009). Cultural icons and marketing of gambling. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7(1), 84-96. doi:10.1007%2Fs11469-007-9145-x

Gainsbury, S., Aro, D., Ball, D., Tobar, C., & Russell, A. (2015). Determining optimal placement for pop-up messages: Evaluation of a live trial of dynamic warning messages for electronic gaming machines. International Gambling Studies, 15, 141-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2014.1000358

Gainsbury, S. M., Russell, A., Hing, N., Wood, R., & Blaszczynski, A. (2013). The impact of internet gambling on gambling problems: A comparison of moderate-risk and problem Internet and non-Internet gamblers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(4), 1092-1101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0031475

Gambling codes of practice [Northern Territories of Australia] (2019). https://nt.gov.au/industry/gambling/gambling/gambling-codes-of-practice/nt-code-of-practice-for-responsible-online-gambling-2019

Gehlert, S., & Ward, T. S. (2019). Theories of health behavior. In S. Gehlert & T. Brown (Eds.), Handbook of health social work (pp. 43-163): Wiley.

Ginley, M. K., Whelan, J. P., Keating, H. A., & Meyers, A. W. (2016). Gambling warning messages: The impact of winning and losing on message reception across a gambling session. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30, 931-938. https://doi:10.1037/adb0000212

Ginley, M. K., Whelan, J. P., Pfund, R. A., Peter, S. C., & Meyers, A. W. (2017). Warning messages for electronic gambling machines: Evidence for regulatory policies. Addiction Research & Theory, 25, 495-504. 10.1080/16066359.2017.1321740

Government of Canada (2019). Cannabis health warning messages. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/laws-regulations/regulations-support-cannabis-act/health-warning-messages.html

Hancock, L., & Smith, G. (2017). Critiquing the Reno Model I-IV international influence on regulators and governments (2004–2015) – the distorted reality of “responsible gambling”. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s11469-017-9746-y

Horstmann, G. (2015). The surprise-attention link: A review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1339(1), 106-115.

Internal Affairs [New Zealand] (undated). Gambling fact sheet #6; Gambling harm prevention & minimisation. https://www.dia.govt.nz/diawebsite.nsf/Files/Gambling-Fact-Sheets-Aug2015/$file/FactSheet6-August2015.pdf

Jardin, B. F., & Wulfert, E. (2012). The use of messages in altering risky gambling behavior in experienced gamblers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26, 166-170. https://doi:10.1037/a0026202

Kihlstrom, J. F. (2013). The person-situation interaction. In D. E. Carlston (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of social cognition (p. 786–805). Oxford University Press.

Keogh, B. (2019, June 20). Gaming and gambling link: Call for warning label over video game “loot boxes. https://www.stuff.co.nz/entertainment/games/113599005/gaming-and-gambling-link-call-for-warning-label-over-video-game-loot-boxes

Malouff, J., Schutte, N., Frohardt, M., Deming, W., & Mantelli, D. (1992). Preventing smoking: Evaluating the potential effectiveness of cigarette warnings. Journal of Psychology, 126(4), 371-383.

Markham, F., & Young, M. (2014). “Big gambling”: The rise of the global industry-state gambling complex. Addiction Theory & Research, 23. 1-4. https://doi: 10.3109/16066359.2014.929118

McGivern, P., Hussain, Z., Lipka, S.,and Stupple, E. (2019). The impact of pop-up warning messages of losses on expenditures in a simulated game of roulette: A pilot study. BMC Public Health, 19, 1-8. https://doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7191-5

Miltenberger, R. F. (2016). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures (6th ed.). Cengage.

Munoz, Y., Chebat, J. C., & Borges, A. (2013). Graphic gambling warnings: How they affect emotions, cognitive responses and attitude change. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29, 507-524. https://doi:10.1007/s10899-012-9319-8

NSW Department of Industry Liquor & Gambling (2018). Student notes. www.liquorandgaming.nsw.gov.au/documents/collateral/RCG_student_manual.pdf.

Pfizer (2013). Zoloft. http://www.pfizer.com.au/sites/g/files/g10005016/f/201311/CMI_Zoloft_521.pdf

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. (2004). Role of culture in gambling and problem gambling. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 1087-1114. https://doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.005

Signage requirements for gaming areas [Victoria} (undated). https://www.cbs.sa.gov.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/signage-requirements-for-gaming-areas.pdf?timestamp=1576803383231

Savage, M. (2018, May 27). Gambling ads must have serious addition warnings, demand MPs. The Guardian.

Sonderegger, A., & Sauer, J. (2010). The influence of design aesthetics in usability testing: Effects on user performance and perceived usability. Applied Ergonomics, 41(3), 403-410.

United States Code of Federal Regulations, 16.21 (2020). Mandatory label information. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2019-title27-vol1/xml/CFR-2019-title27-vol1-part16.xml

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2020). Cigarette labeling and health warning requirements. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/labeling-and-warning-statements-tobacco-products/cigarette-labeling-and-health-warning-requirements

Welte, J. W., Tidwell, M. C. O., Barnes, G. M., Hoffman, J. H., & Wieczorek, W. F. (2016). The relationship between the number of types of legal gambling and the rates of gambling behaviors and problems across US states. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32, 379-390. https://doi:10.1007/s10899-015-9551-0

Wood, W., & Rünger, D. (2016). Psychology of habit. Annual Review of Psychology, 67. 289-314. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417

Xie, W., Bainbridge, W. A., Inati, S. K., Baker, C. I., & Zaghloul, K. A. (2020). Memorability of words in arbitrary verbal associations modulated memory retrieval in the anterior temporal lobe. Nature Human Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0901-2

Young, J. M., Stacey, I., Dobbins, T. A., Dunlop, S., Dessaix, A. L., & Currow, D. C. (2014). Association between tobacco plain packaging and Quitline calls: A population‐based, interrupted time‐series analysis. Medical Journal of Australia, 200(1), 29-32. doi: 10.5694/mja13.11070

Table 1

Types of gambling warnings recommended by experts on problem gambling

Warning category and sample warnings

___________________________________________________________________

Gambling is risky; gamblers will likely lose money and may experience problems

Gaming machines can lead to severe financial losses.

The more you gamble, the more you lose.

The gambling activities available on this site are designed to make a profit. The more you gamble, the more likely it is to become a problem.

Betting can lead you to lose everything, including dignity.

(Provide statistical risk information for the specific type of gambling.)

(Inform about the mathematical expected value of the product (e.g., ‘This machine retains on average 25% of the money users gamble”).

The structure and layout of gambling establishments and the games themselves encourage riskier forms of decision making in some patrons.

Specific advice about how to minimize losses and avoid problems

Take frequent breaks from gambling by leaving the building or logging off your computer.

Gamble only with a fixed budget and for a predetermined period of time.

(Hotline, website, or other contact info here.)

If you feel bad or anxious about losing money, but continue to gamble, reach out for help.

Reflect on your gambling

What else might you have bought for the money you lost to gambling?

Are you gambling for more money than you intended to?

Are you honest to family and friends about how much you spend on gambling?

Do you know what drives you to bet? The compelling prospect of an immediate win that will lead you to bet again (and again), without regard for the negative consequences that excessive gambling will have on your life.

Compare your gambling level to norms

Most people do not gamble every day, or even every week.

Do not exceed gambling norms.

Gambling is addictive

Gambling can be addictive.

Gaming machines are incredibly addictive. Once addicted, you may not be able to stop even when experiencing harms.

Gambling, like alcohol, may result in addiction leading to significant harms to the individual and their families.

Gamble only if it is fun

Gamble only if you find it fun.

Stop gambling when you are no longer having fun.

Avoid emotional gambling

Never gamble when you are feeling sad, upset, or are under the influence of alcohol or other drugs.

Sometimes gambling isn’t about just gambling—sometimes it’s about your mental health being off.

Pokies (Electronic gambling machines) won’t make a bad day better.

Amulets do not help

Amulets do not help.

It is no use having amulets, rituals, a favorite number or color. The odds are always against you.

Image by Christine Schutte-Malouff

0 Comments