Interview with Amy Hammond

White people say that we have no culture, but then, they have our stuff locked away in museums and private collections all over the world.

Amy Hammond is a Gamilaroi mother and community member, working to reclaim Gamilaroi weaving knowledge and to pass these stories and cultural practices on to the next generation. Amy is also an Indigenous Early Career Fellow at UNE who, early in 2018, undertook a research trip to examine collections of Aboriginal artefacts held in museums in London, Paris and Florence. The aim of the trip was to identify any Gamilaroi weaving in these collections because, as Amy has found out, there are collections of Gamilaroi weaving held around the world both in museums and private collections.

What do you think of when you see all those Aboriginal artefacts locked in cupboards on the other side of the world?

It’s theft. Regardless of whether it was taken in the past, or donated to a museum more recently through a private collector, it is still theft. Our families and communities were not fully informed of where it was going, or what was happening to it, so it’s stealing across the board. Many museums couldn’t

tell us who was the owner of the items or exactly where they came from. We were in London, then Paris, and the last stop was Florence; to the University there. It was the only place where I cried. I was just so tired by the end of that journey, and everywhere I went there was stuff from home. I just walked over to the cabinet and said, “what are you doing in here? We want you to come home”.

I was shown a lot of the artefacts that were on display and in storage, but we also know that they are in possession of many more sacred things like ceremonial objects and the remains of our family members. I travelled a long way and opened boxes that had not been opened in 100 years and inside were our stories woven, carved and painted. Everywhere I went over there, I just saw us – it was disturbing. When we weave, we weave energy into each piece. Somebody put energy into all those things, somebody spent time and energy, putting it into the boomerangs, and all the different objects that were there.

Can you talk a bit about the cultural impact of having all those artefacts so far away?

Growing up, I was told especially in school, that we don’t really have culture, told that we were halfcast blacks and nothing like the ‘real’ Aborigines. White people say that we have no culture, but then, they have our stuff locked away in museums and private collections all over the world. We were looted, absolutely looted. There are a lot of conversations all over about repatriation, about giving objects back, but…

Unfinished Bag — woven lomandra bag by Amy Hammond. The unfinished bag is a response to the unfinished bags of Australian Aboriginal peoples being held in museums around the world. Why didn’t they get finished? This bag represents Gomeroi weaving being interrupted.

Did that come up while you were there

Yes, yes it did, but they were all like, well, you know, we don’t have much here but you should see what they have in the next museum, or you should see what they have in Florence. It was a big finger pointing thing. There were current discussions at Cambridge already about a particular spear, about that going back to its community. So there are conversations, so yeah, it’s happening, but very slowly. But you know every single museum I’ve been to, none of them know what they have. They could not tell me exactly where the items came from or even what it was made out of. None of them. None of them could tell me at the time. None of them have a complete database. But they just have so much. That goes for collections all over the world. It’s all just ‘stockpiled’, is the word that’s used! But getting stuff back is not simple or easy. They explained to me at Cambridge that even if there were artefacts, say two of the same thing — like clapping boomerangs, something that was a pair, then they would separate them and, because they already have one, they would use the other to trade for other artefacts. It’s a really common thing. So even if you get things back, so many things have been separated. Because it’s used as a trading tool, between museums around the world, so they could be anywhere.

How did seeing the artefacts influence your research?

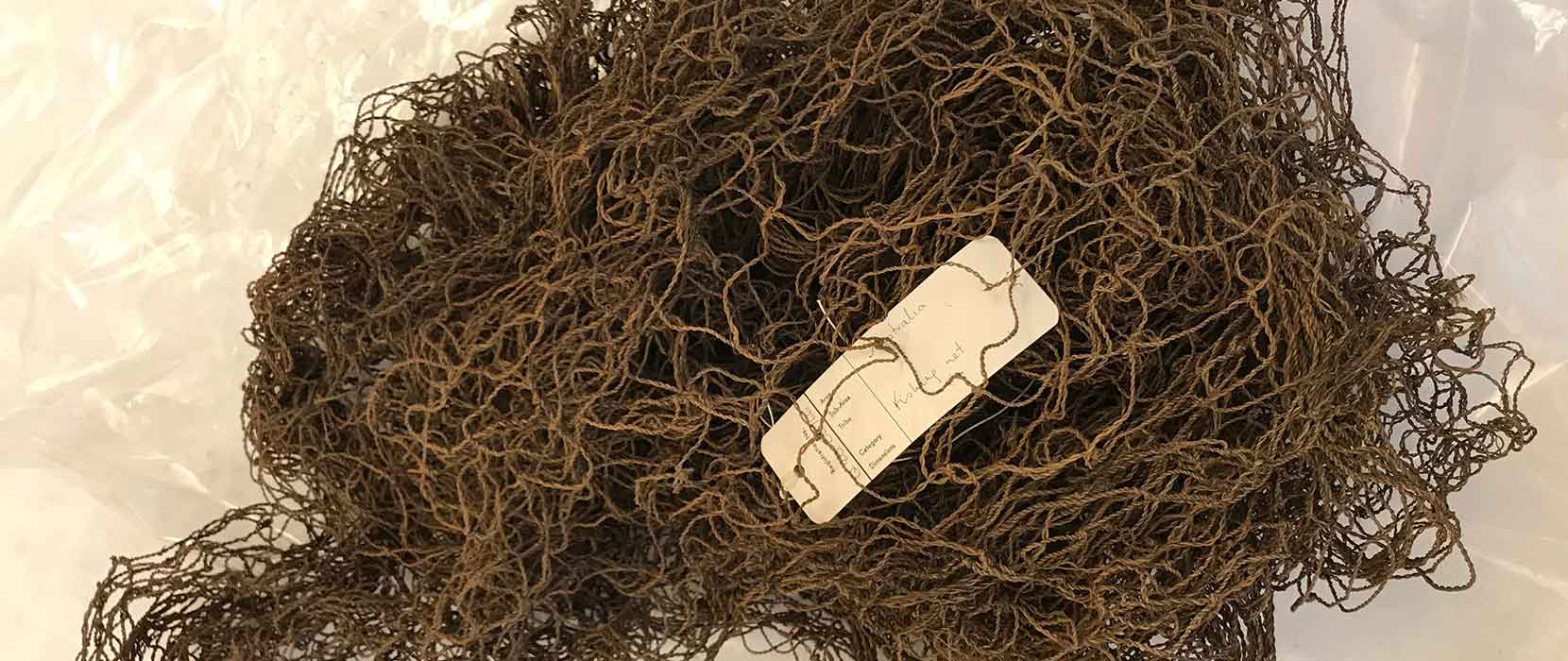

Part of my research involves weaving nets. And now I have seen a lot of nets, a lot from New South Wales. So what Iook at is, obviously, the loop, the stitch, how thick the rope is, so I can compare all these different nets, and I can look at similarities, differences, things like that. Particularly the thickness. So I am going to now make the thickness of the net to match the ones that I have seen. So it’s really valuable to have had that access and see woven artefacts, and it will have an impact on the practical, making side of the weaving research.

But it also makes me realise just how much they don’t really care about us: our families’ belongings because they don’t even know what they have. The box that had not been opened for nearly one hundred years, how can they justify keeping everything when they are not even looking at it. It means nothing to them.

What would you like to see with these collections?

They need to come home. Everything needs to get returned. It’s wrong. They have artefacts on display that are not meant to be seen. They have women’s stuff , men’s stuff , ceremonial things that, frankly, should only been seen by the people who know what they are and know how to keep them safely. It should be up to the appropriate and knowledgeable people in our communities, on how things are displayed, and where they’re kept. Because it’s our responsibility, it’s our country, everything comes from country. It all needs to come home.