Not all species presumed to be extinct are gone forever — there are remarkable Lazarus-like tales of rediscovery, and many of these come from our own continent.

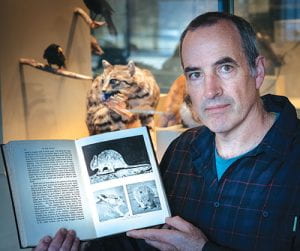

Associate Professor Karl Vernes

School of Environmental and Rural Science.

How many species are there currently alive on Earth today? If you don’t know the answer, that’s OK – nobody does. New species are steadily being discovered, and others, sadly, have been sent to – or are rapidly on the way to – extinction. We are currently at the beginning of one of the Earth’s great mass extinction events – just the sixth one known in the history of life on Earth, but this one is different because of its strong link to our species, and the changes we have wrought on natural ecosystems. However, not all species presumed to be extinct are gone forever – there are remarkable Lazarus-like tales of rediscovery, and many of these come from our own continent.

Associate Professor Karl Vernes has spent the last 12 months looking for an enigmatic mammal presumed to be extinct, called the desert-rat-kangaroo (Caloprymnus campestris).

Associate Professor Karl Vernes has spent the last 12 months looking for an enigmatic mammal presumed to be extinct, called the desert-rat-kangaroo (Caloprymnus campestris).

“This animal has a history of extinction and rediscovery. It was first described in 1863 and then immediately ‘lost’ to science, rediscovered around 1905, lost again, before another cycle of rediscovery and loss in the 1930s” said Associate Professor Vernes.

“Since it was last collected in the 1930s, reports of a small kangaroo fitting the animal’s description have continued to emerge, with the most recent being a compelling eyewitness account from 2013”.

Spurred on by these accounts emanating from a remote and poorly-studied region, Associate Professor Vernes mounted a crowd-funded expedition in 2018 to follow-up reported sightings, and to survey potential habitat that has received little scientific attention.

One caveat of listing a species as ‘Presumed Extinct’ is that it must first have been the focus of exhaustive surveys undertaken throughout its historic range. Associate Professor Vernes feels this has never been done for the desert rat-kangaroo, which is what his research seeks to redress. During two expeditions to the Sturt Stony Desert, he and field team deployed nearly 60 camera traps that gathered thousands of photographs of any animals that wandered into the cameras’ field of view, collected over 300 predator scat pellets containing the hair and bones of a dingo, cat, or fox’s last meal, and undertook spotlighting surveys for hours each night they were in the desert. So far, visual surveys with cameras and spotlights haven’t been successful in finding the species, although the work did uncover a new population of another threatened desert marsupial, the kowari (Dasyuroides byrnei), more than 100km south of any known population. The predator scats are still being analysed by an expert who can describe, to species level, the remains found in these pellets.

In 2019, the research will take an exciting new angle; Associate Professor Vernes will join a team of scientists that will travel by camel into the Simpson Desert, visiting landscapes even more remote than those already surveyed.

“We don’t know what we will find” he said, “but as a conservation biologist, I feel we owe this unique little desert marsupial the effort of searching for any remnant populations. Australia can present serious difficulties for biologists looking for the last of a species – it is large, contains vast remote landscapes, and is sparsely populated by people. We’ve only really begun the journey to answering the question of whether this animal is still out there”.