OUR PRECIOUS TRADITION OF CARTOONING

One only has to look at the situation across the globe to understand how precious our tradition of cartooning truly is.

Associate Professor Richard Scully Historical Studies, Faculty of Humanities, Arts, Social Sciences and Education

UNE’s Associate Professor Richard Scully is at pains to suggest that political cartoons are so much a part of Australian journalism (and of politics) as to be easily taken for granted. ‘To do so is fraught with danger. One only has to look at the situation across the globe to understand how precious our tradition of cartooning truly is’.

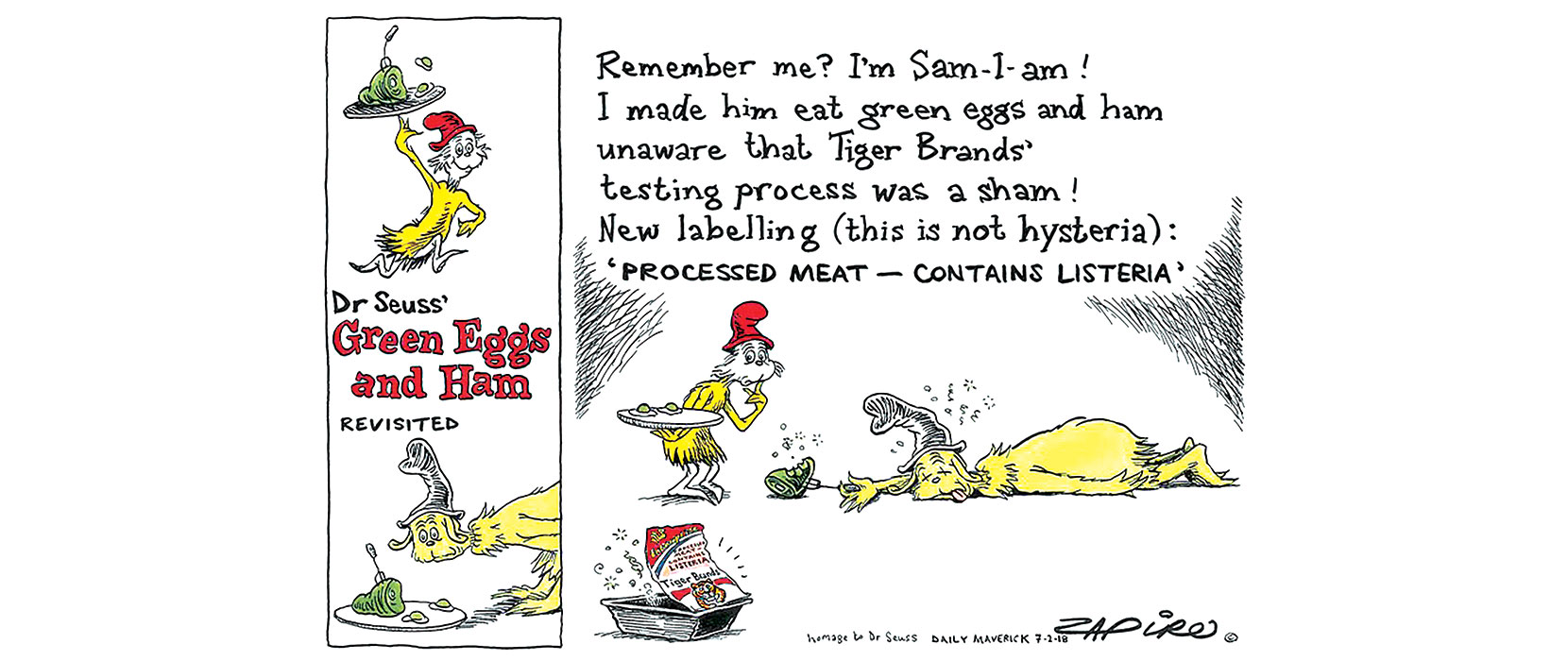

The existence of a flourishing cartoon culture is very much a thermometer for measuring the health or otherwise of a free and liberal press culture; and, therefore, a free and liberal political and socio-economic system. In South Africa, the

continued ability of ‘Zapiro’ (Jonathan Shapiro) to criticize the dominant ANC government of Jacob Zuma, brings balance to

what would otherwise be a decidedly oppressive situation. So too, in Kenya, ‘Gado’ (Godfrey Mwampembwa) stands as one of the greatest champions of democratisation and freedom of expression in an increasingly authoritarian context.

The heroism of these actors is a world away from the newspaper offices of Melbourne, Sydney, and the other capitals, where cartoonists are largely at liberty to say what they like about whoever they like; despite what the opponents of Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act would have one believe.

There are no easy answers in this increasingly complex environment. And as always, what makes for a good cartoon—and a healthy cartoon culture—is all about balance. The home desktop of ‘First Dog on the Moon’ (Andrew Marlton) is unlikely to be subjected to political repression. But terroristic assault? Nobody expected the tragedy of 2015 to affect French

magazine Charlie Hebdo in such horrific fashion as reported in the media. In 2006, Charlie Hebdo’s editors had dared to

reprint the controversial ‘Mohammed Cartoons’ of the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, and driven-home a sustained assault on radical Islam and Sharia Law that often crossed the line between fair comment and outright, calculated insult.

How far are cartoonists willing to go? How far should they go? Are there limits to liberty of expression and free speech? These questions are both timeless and timely.

The very transnational—and indeed, global—nature of the fallout from this great cartoon tragedy is an indicator that

the world is changing. Thanks to the internet, what might be considered fair comment in one country can so easily attract the attention of those in another country for whom ‘blasphemy’, ‘treason’ or other terms might more readily be applied. ‘Cartoonists have to be conscious of this, and balance their hard-won right to freedom of speech with their

responsibilities as global citizens’, Scully argues. His recent exploration of those cartoons guilty of ‘Crossing the Line’ (including the fallout from anti-Israel pieces by Gerald Scarfe in the UK, and Glen Le Lievre and Leunig in Australia; R. Prasad’s attack on ingrained racism in Australia in Delhi’s Mail Today; and Fonda Lapod’s ‘The Adventure of Two Dingo’ in Indonesia’s Rakyat Merdeka) indicates that this will only become more pressing as the century unfolds.

Thus, looking forward and warning of the likely shape of cartooning in the future, is grounded in an understanding of the artform’s history. From 2013 to 2015, as part of an ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award project, Richard Scully explored the beginnings of the globalisation of cartooning via the Anglo-American tradition of the period since 1720. As technology and print culture changed across the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, nevertheless the purpose of the political cartoon has remained stable: to puncture the pompous, to ridicule the self-important, and provide a more realistic and truthful antidote to political spin. Regimes of censorship (e.g. in France under Napoleon III), or the attempt by authoritarian regimes to co-opt the cartoon for their own purposes (e.g. in Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union) may have failed in the past. But this does not mean that the future will always be bright.

Would Donald Trump – tired of the ‘fake news’ encapsulated in the myriad cartoons imagining him as an emperor without clothes – be above enforcing a new and threatening set of press laws designed to gag America’s cartoonists? Might he collaborate with his buddy, Vladimir Putin, who has done so well to co-opt cartoons for his own purposes? Or with the Chinese government, where cartoon culture thrives, but only within circumscribed limits?

The future of cartooning may not look terribly different from its past. But the continued existence of a flourishing cartoon culture should never be taken for granted. That is why the continued study of cartoon history is so important. And, as Associate Professor Scully has found, there is never a dull moment in this still-neglected area of inquiry.