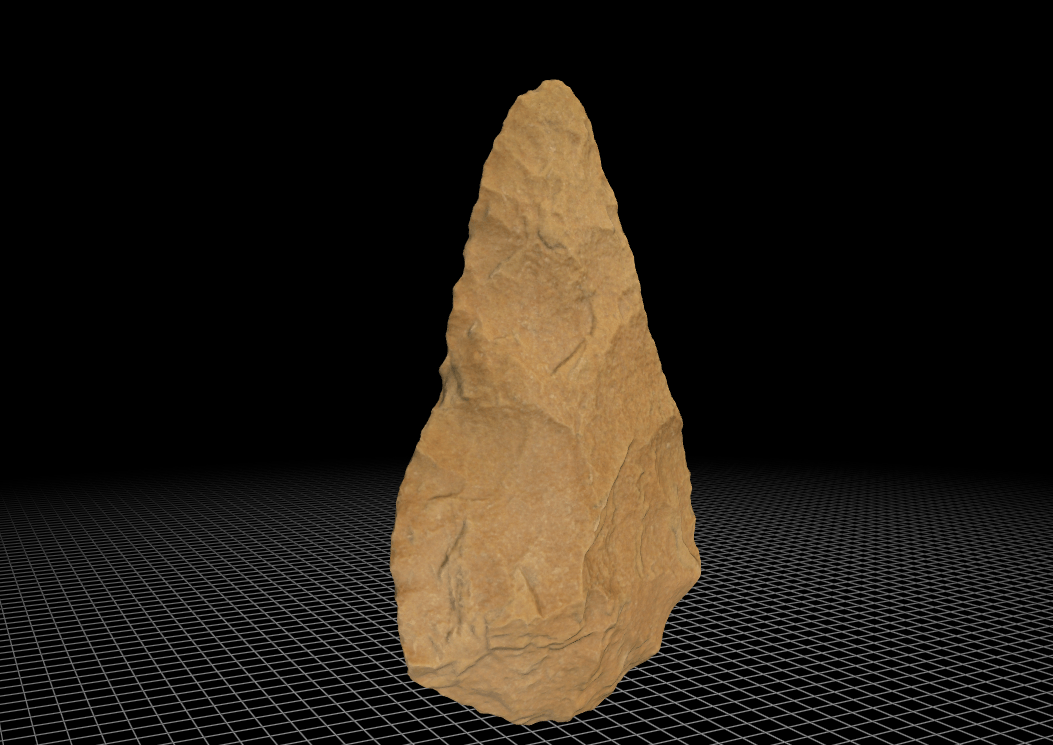

Image: Digital scan of a Quartzite Late Acheulean handaxe from North Africa, provided by Professor Mark Moore.

How much do you know about ‘Cognitive Archaeology’?

This curious area of study explores how the human mind has evolved and developed cognitive complexity going back to our inception as a genus. One of the most common ways to investigate this is through the examination of how early humans behaved, particularly stone tool manufacture. UNE’s Professor Mark Moore has been researching in this fascinating field for many years, and has recently set off on a research project to explore what the manufacturing of stone tools has to say about early human cognition.

“I was lucky enough to be successful in the Future Fellowship round of the Australian Research Council last year to fund my research,” said Professor Moore. “The project kicked off on February 1st, so it is early days yet, but this research involves conducting experiments and doing field work, primarily in the United States, but also Indonesia and possibly India, depending on the COVID situation.”

This research seeks to provide a better understanding of the relationship between early stone tool manufacturing and the cognitive evolution in early humans. While it is often thought that the build-up of complexity in stone tools within the archaeological record illustrates how the human mind evolved, Professor Moore’s research may suggest otherwise, or at the very least, that it isn’t as simple as that.

“My first generation of experiments sought to unpack these arguments and get an empirical understanding of how we can characterise complexity in stone tool manufacture, and the results of that were very surprising,” said Professor Moore.

“I found that, within controlled experiments, randomising the way that flakes were removed from a stone was producing a lot of what archaeologists infer are complex stone tools, but I was doing it using a random number generator. So that suggests that there is something very wrong with some of our understanding of the earliest hominin cognition based on these stone tools.”

“It is very exciting to be working in this space. This is the only research lab in the world that is doing this kind of research at this moment.” – and this is only the beginning of Professor Moore’s research. Throughout this project many interesting avenues will be explored, for example the contemporary practice of ‘flint knapping’. Luckily, Professor Moore has been a flint knapper for thirty years.

“There are actually several thousand flint knappers, particularly in the United States and Europe that do this as a hobby. A gatherings of flint knappers is what is referred to as a ‘knap-in’ and this is when you get several dozen flint knappers together in one spot and they share their insights, tricks and techniques on how to achieve the effects needed to make certain types of stone tools.”

“I am interested in observing those master flint knappers at work to see exactly what they are teaching, how that teaching process works, to what extent it is verbal and to what extent it is visual. That will give us some insights into the way that aspects of the stone tool design space has been passed down through the generations.”

While discussing the stone tool designs and manufacturing complexities that suggest cognitive evolution in early humans, Professor Moore brought up the ‘Acheulean handaxes’.

“What I found in my early experiments is that I could produce aspects of these handaxes with a random number generator, I was getting objects that archaeologists would classify as a crude or primitive handaxe. What I am going to do now is change the original experimental protocols to figure out what aspects I can change to get us a little bit closer to things, like handaxes. I will loosen some of the experimental rules like using a random number generator. I’ll relax that and come up with ways that flakes can be removed in sets, for instance.”

The study of stone tool manufacture is beyond a curiosity to Professor Moore – it is both a personal interest and professional passion, one that he is eager to share with others, including students.

“One of the things that I try to do is a lot of public outreach on stone tools and stone tool manufacture, so I established with some students about five years ago, what we called the Australasian Flint Knapping Guild. We meet every Wednesday at lunchtime just to sit around and make stone tools and chat about all kinds of things.”

Recent Comments